Blue Plaques Honour Remarkable County Durham Women

Blue plaques can be found on buildings, acting as a commemorative link between an individual or event and the location. Offering an historical insight into the lives of individuals, they often make for interesting reading. The Blue Plaque Scheme is one of the most effective ways of publicly celebrating local history, and councils and organisations across the UK have taken inspiration from the original English Heritage-run scheme, which began in London in 1866, to celebrate and recognise the history of their local areas.

In County Durham, the scheme has administered between 20–30 blue plaques: commemorating Charles Dickens, the first edition of the Darlington and Stockton Times, and even fictional characters. Something you won’t find, however, are many plaques celebrating the achievements of local women. The Durham Women’s Banner Group, founded in November 2017, set out to change this with a public appeal for nominations of worthy females.

After discovering a lack of female representation at the Durham Miner’s Gala, the group’s secretary, Lynn Gibson, recognised the need for a Women’s Banner Group in the area. ‘It seemed to feed into a time where there was a lot of female activism about,’ she explains. The group aims to encourage the younger generation to use their voice to make a change in their own lives, and the lives of others, and getting involved in this debate led them to discover the Blue Plaque Scheme in County Durham.

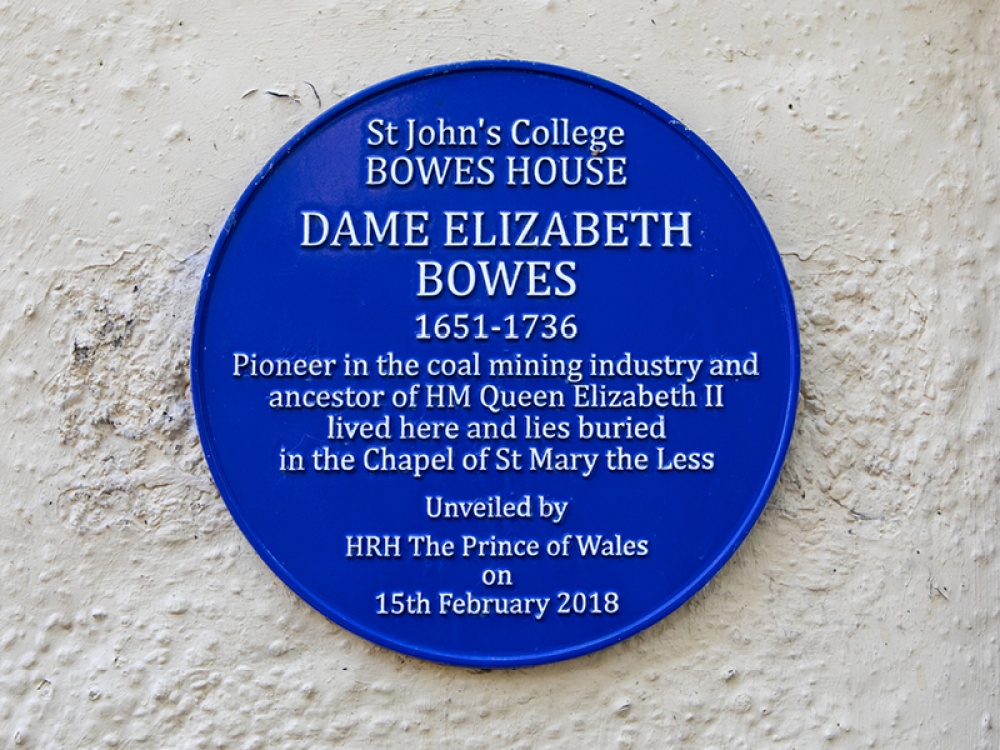

Initially, the group were unaware that County Durham’s only existing plaque to commemorate the achievements of a local woman was on the wall of St John’s College at Durham University, to celebrate Dame Elizabeth Bowes, a pioneer in the coal mining industry. ‘If you search for female blue plaques in Durham, you won’t find anything,’ says Lynn. ‘There’s no mention of that plaque in the University press, and not a single newspaper article refers to the plaque as being the first ever for a female in the area.

‘We spoke to the council about where the blue plaques were, and found that there were around 30 in the county currently. They’re all men, buildings, and even fictional characters are being recognised before women.’

Over the last two years the Banner Group have focused their work on celebrating the role of women during the time of the miners’ strikes in 1984, and the achievements of women since then. Their Blue Plaque Project has striven to publicly recognise these women.

While the ultimate goal was to put forward the top nominated individual to Durham County Council, with the hope of erecting a plaque in honour of their achievement, the group uncovered a wealth of stories about local women through a hustings and nomination event – where all of the nominations proved worthy. But despite a vast amount of support for the project, the general lack of historical knowledge about women in the area meant it took a lot of time to research.

Starting off with appeals for nominations, the local community came together to discuss those women they deemed most worthy of a blue plaque. ‘Obviously the idea is that it’s not just someone’s mum who makes an amazing apple pie,’ explains Lynn. Nominations were made by children from Belmont School, local politicians, and the wider community. ‘We received seven nominations at our hustings event, and everyone there then voted for a single winner,’ Lynn explains. Elizabeth Pease Nichol, an abolitionist, came out top – however, the group discovered she was originally from Darlington, and strict regulations state that she wouldn’t fall under the Durham County Council Blue Plaque Scheme. Turning to second place, the group found there was a three-way tie, and so decided to submit a formal request to Durham County Council for all three.

Name: Kate Maxey

Occupation: Nurse

Suggested Plaque Location: Her father’s shop, which now operates as Defty’s at 25-27 High Street, Spennymoor, County Durham

Born in Spennymoor in 1876, Kate Maxey (who was always Maxey and never Kate), became one of the most highly-decorated nurses of the First World War. Maxey trained and worked at Leeds General Infirmary, qualifying in 1903. Shortly after war broke out, she was sent to Rouen, France, and from then until March 1918, she gave an unstinting and distinguished service at several hospitals on the Western Front. In 1916, Maxey was promoted to Sister and, in September 1917, was appointed Sister in Charge of the 58th Casualty Clearing Station at Lillers, France. It was there, in March 1918, that she was severely wounded during a bombing raid. An ammunition train exploded near the casualty station and she sustained multiple bomb wounds to the forehead, neck, right leg, as well as a broken arm and a spinal injury.

As one of the first territorial nurses to go France, Maxey qualified for the 1914 ‘Mons’ Star. The 1914 Star, as it’s also known, was a campaign medal of the British Empire for services in World War One. In 1918, she was awarded the Royal Red Cross First Class for distinguished service in the field and gallantry during the bombing raid. The Military Medal was also awarded to her in 1918 for bravery under fire. Additionally, in 1920, Kate was one of the first recipients of the Florence Nightingale Medal – awarded by the International Red Cross Committee ‘for nursing services from 1914–1918 especially at No. 58 Casualty Clearing Station.’ She is also listed as one of those who served with distinction in Spennymoor Urban District Council’s Book of Remembrance, prepared for the opening of the Cheapside War Memorial in 1922.

Kate’s career in nursing lasted for over 30 years and her three-and-a-half years serving on the Western Front contributed greatly to the welfare of her patients. Her Commanding Officer at 58 Casualty Clearing Station, Lieutenant colonel J Graham Martin, later an Honorary Physician to King George V, wrote in March 1918: 'Miss Maxey's tact, zeal for work, and influence for good are of the highest order. On the night of 21 March 1918, when lying wounded, she still directed nurses, orderlies and stretcher bearers, and refused aid until others were seen to first. I have the greatest pleasure in giving this testimony to one of the finest Nursing Sisters I have ever met.'

Name: Lady Bella Lawson

Occupation: Parish Councillor and School Manager

Suggested Plaque Location: Bella Lawson’s home, Beamish, Stanley

A passionate pioneer and promoter of Child Welfare Clinics from 1919 until her death in 1968, Bella Lawson assisted in setting up Labour Women’s Sections from 1918, and established the Durham Women's Advisory Committee in 1920, which worked hard as a pressure group to campaign for better housing. Bella, and many other women, acted as unpaid volunteers to run these clinics and, as a result, the health of innumerable women and babies greatly improved. Spending her entire life as a volunteer in a number of organisations, always wanting to help other people, Bella took on roles such as Parish Councillor, School Manager, member of the Worldwide Veterinary Service, with the National Savings’ Worker’s Educational Association, and the Save the Children Fund, amongst many more.

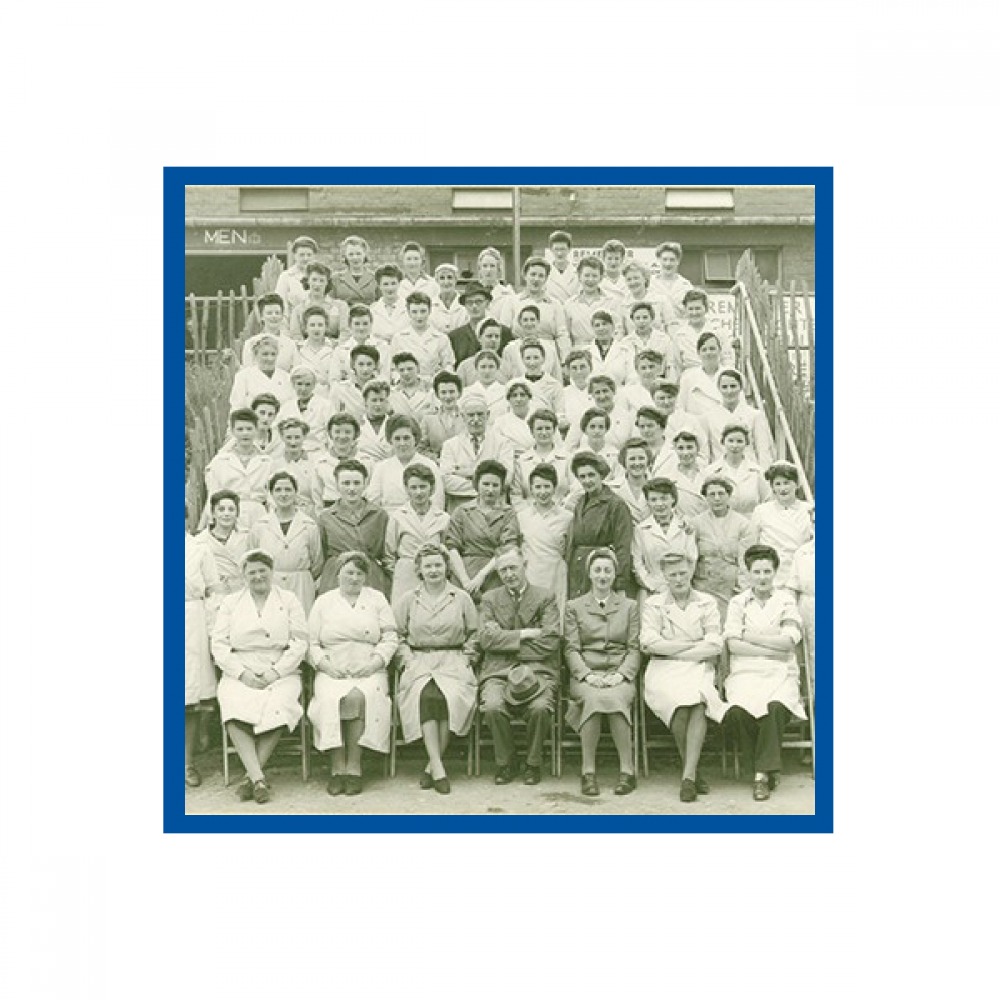

Name: Aycliffe Angels

Occupation: Munitions Workers

Suggested Plaque Location: ROF59, the main site of the Angels’ work, which is now a climbing centre, trampolining park and community space

Originating in Aycliffe and the surrounding areas, the Aycliffe Angels were munition factory workers, numbering around 17,000, who were all highly regarded for their contribution to the region’s war efforts. Filling shells and bullets, and assembling detonators and fuses for the war effort during the Second World War, their operation – which was carried out for just over four years – produced over 700 million bullets and countless other munitions. Despite being visited during the war years by Winston Churchill and members of the British Royal Family, the factory was deemed a ‘top secret' installation, surrounded by high fences with barbed wire. By its nature, the work was very dangerous and many were killed and injured during the manufacturing process. However, due to the secrecy surrounding the factory and its workers, incidents went unrecorded and unreported – leaving the Angels’ efforts unrecognised.

While all of their stories are profound, Durham’s Women’s Banner Group discovered the process of attaining a blue plaque isn’t all that easy. Stringent guidelines for the erection of a blue plaque – 20 years must have passed since a candidate’s death; the building hosting the plaque must survive in a form that the commemorated person would have recognised; and buildings with many personal associations, such as churches, schools and theatres, are not normally considered for plaques – create a number of reasons for the nominations to be rejected.

‘It’s just a waiting game now,’ says Lynn, ‘but as far as we could tell, our submissions fit the strict criteria. It’s up to the panel to decide.’

While the group have paved the way for the potential establishment of three blue plaques for women in County Durham, Lynn emphasises that their choice to submit the top three nominated ladies shouldn’t discourage others from making their own nominations.

For more information, or to nominate someone for a blue plaque, visit www.durham.gov.uk