How This Sunderland Artist Hopes Her Campaign Will Save the National Glass Centre

Living North learn more about a campaign to save the National Glass Centre, which is facing potential closure

Sunderland’s National Glass Centre is a cultural venue which showcases the city’s rich glass making heritage whilst also keeping glass making skills alive. Inside you can meet resident glass makers who create their art there and offer daily glass demonstrations, explore the exhibition spaces to see work by some of the world’s finest contemporary glass and ceramic artists, and take part in various workshops to learn or hone your own creative skills. It’s also home to the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art.

Jo Howell is a University of Sunderland alumni, having graduated with her degree in Photography, Video and Digital Imaging in 2009. Since then she has been running her own business and working on commissions. ‘I’ve worked freelance for the National Glass Centre both as an educational institution and also as a commercial photographer (photographing people’s glass artwork),’ she tells us. ‘I’m also engaged to Phil Vickery [an award-winning glass artist] and for the last 14 to 15 years he’s been hiring the National Glass Centre’s equipment to create his artwork. One of the main reasons my partner and I have stayed in Sunderland is so he could have that access so he could continue his career.’

The National Glass Centre, which opened in 1998 and is now owned by University of Sunderland, is set for potential closure in 2026 due to costly repairs but Jo and her recently-formed campaign group are fighting to save the iconic building. To find out why this is so important to Jo, the local community and the city’s cultural heritage, we learn more about Sunderland’s history of glass making.

‘The Romans brought glass to Britain,’ Jo tells us. ‘But as far as we can tell it was imported from other provinces. We weren’t making glass under the Romans, but it was here.’ The first stained glass to be produced in Britain was made in Sunderland by French craftsmen who came from Gaul in 674AD. Anglo-Saxon abbot Benedict Biscop (founder of Wearmouth-Jarrow Priory) brought in these skilled craftsmen to create the first stained glass window in England for St Peter’s Church in Monkwearmouth. ‘It was part of the Christian Enlightenment,’ Jo says. ‘If you put yourself back in time, they didn’t have anything that was really colourful, bright and awe-inspiring, and they didn’t have many buildings which were made out of stone. Biscop brought specialist glaziers across from Gaul and they made the glass in situ and showed the Saxons how to make glass. That’s when it started, so we’ve got a very definite date of 674AD. This year should’ve been a big marking point which we would’ve been celebrating had we not have been facing the [potential] loss of the National Glass Centre.

‘Since 674AD there’s always been some form of glassmaking and pottery on the River Wear. We had a big boom during the industrial revolution and we were making a lot of money from mining coal and putting it on ships that we’d built and sending it across the world. Quite often, the way that the ships worked would be that they were ballasted with really good quality sand so we had this tri-sector between mining, ship building and then glass blowing because one of the main ingredients in glass is fine quality sand. We were essentially using waste products from the bigger industries of ship and coal to create glass.’

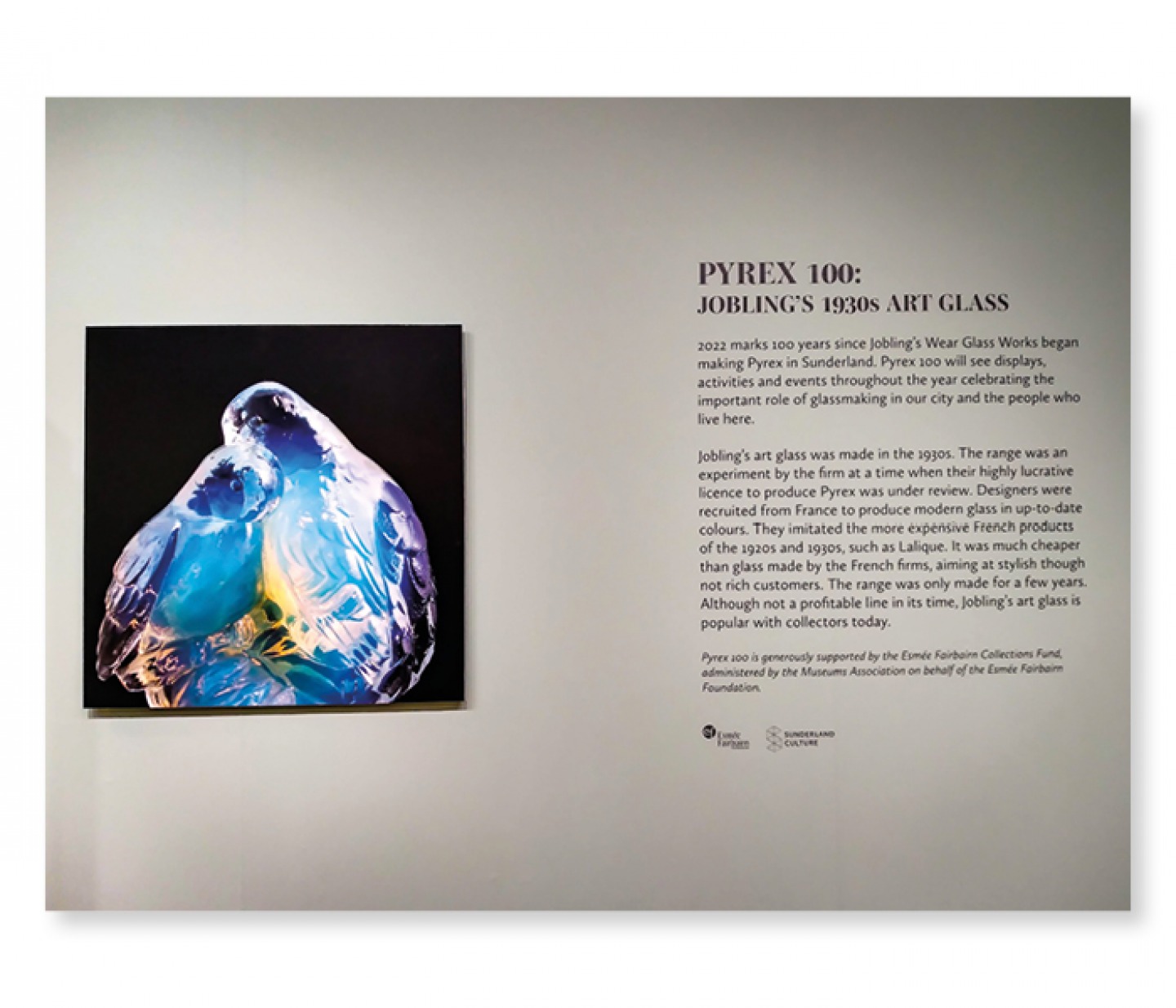

In the 1920s, Ernest Jobling-Purser of James A. Jobling and Co found potential in Pyrex and secured the licence to make it at the Wear Glass Works and sell it across the British Empire. ‘Pyrex is quite robust and lots of people are still using Pyrex in their own homes,’ Jo says, and many Sunderland residents have memories of working in the Pyrex factory over the years. ‘The thing with Pyrex was that it changed the structure of glass so that it could take temperature changes better.’

Sunderland's last remaining shipyard closed in 1988 and the final mine closed in 1993 (Monkwearmouth Colliery, which was where the Stadium of Light is now). But it wasn’t long after this that the National Glass Centre was born. It was the recipient of the first major Arts Lottery Award in the North East and was the first Arts Lottery-funded building. ‘The conversations surrounding the National Glass Centre started in around 1992 with the closure of the last mine and in 1998, when it was opened by the then Prince Charles, it was an iconic building,’ Jo adds. ‘Built to memorialise the loss of the shipyards, it’s a similar shape to a ship and was also built on a slipway to the old shipyard.’

The National Glass Centre was in private hands and was run by independent bodies at the time. ‘In 2007 the Pyrex factory in Sunderland closed down, University of Sunderland took over the National Glass Centre in 2010, and in 2012 and 2013 there was more money put into the National Glass Centre from the Arts Council to do another refurbishment and to bring in future-facing electric furnaces. Prior to that all the furnaces had been gas-run. For years it was doing amazing stuff. It was a great way for Sunderland to apply to be the City of Culture too. If you’ve got a national centre and you’ve had it for a while you can use that as your anchor. We didn’t get City of Culture but we did, off the back of that, get Sunderland Culture, which is a sister organisation to University of Sunderland and a charity. Over the last 25 years the National Glass Centre building and the people in it have created a magnet effect – there have been other skills, wonderful glassmakers, photographers, filmmakers and musicians that have been able to come here because of the opportunities it has offered.’

Jo is passionate about continuing the celebration of this heritage and supporting Sunderland’s resident glass makers who are keeping these skills alive. ‘It’s so important because there’s so much history interwoven in the people of Sunderland and even the landscape itself that if you can’t get this history, you’re missing all the nuance and the beauty of it,’ she explains. ‘The history is important and needs to be raised up and celebrated; and 26 years of prestige as a national centre is not really that easy to come by, so as a globally-facing asset the National Glass Centre is really unique and an absolute treasure. The building is award-winning and it has an iconic silhouette on the skyline. As a photographer and artist myself I’ve used the building so many times as an iconic emblem for my work – and that’s just the exterior, never mind all the fantastic stuff that goes on inside.’

In January 2023, University of Sunderland announced that major repairs were needed to the structure of the National Glass Centre building, including the glass roof. Following a commissioned report, the university believes it could cost between £14 million and £45 million to carry out safety and remedial works. In response to this, Jo is leading the Save the National Glass Centre campaign, and is in the early stages of forming a unified group. ‘I wanted to see who was waiting in the wings so I put out the feelers and it turns out hundreds and hundreds of people were also devastated by the news,’ says Jo. ‘Quite quickly we put together a small team and set about collecting information and people’s thoughts. It’s not just a building, it’s people’s lives and careers. It’s such a unique specialism it’s not like you can just pack up and find a glass blowing centre easily elsewhere. I found there were a lot of people feeling the same as me and we realised that we didn’t actually know much about what the plans were so we were questioning all that.

‘My motley crew of strangers and volunteers got together and I organised a public meeting in June 2023 after I’d met with the board and representatives for University of Sunderland. At the meeting the general public and councillors and MPs turned up and we had people crying because they couldn’t believe what was happening. After that, I got my team together, which is made up of artists, civil engineers, architects, members of the local community and business owners, and as a rag-tag campaign group we’ve had a really excellent letter writing campaign, freedom of information requests to the university and council, lots of meetings, we’ve been to see the Arts Council England, we’ve met with Lord Parkinson and local councillors and we’ve also had a petition which is ongoing because I’m thinking if I can push it to 100,000 [signatures] then I’ll take it to Parliament. We can’t give up. We might as well go for it hell for leather because once the National Glass Centre has gone, I don’t think we’ll get anything close to what we currently have.

‘Essentially I think we’ve come as far as we can as a group of strangers so our next step is to set up a community business society [CBS] which is a better set-up than a CIC [community interest company] because it’s more globally facing. We’re looking at lots of different lines of funding and we need to get ourselves constituted as a group so we can start fundraising, liaising with important organisations and doing things we can’t do as just a group of people.’

Jo is now encouraging members of the public to share their love for the National Glass Centre and the opportunities it has offered. Find our more about the Save the National Glass Centre campaign at savethengc.art.blog. Learn more about the National Glass Centre (which remains open to visit) at sunderlandculture.org.uk.