Learning More About Our Native Grey Seals on World Wildlife Day

Our native grey seals headed closer to shore during the pandemic

The curious face of a grey seal bobbing in the waves is a familiar and welcome sight for us in the North East. With a colony here all year round, these native marine mammals can be seen in the water all the way along our coastline.

Yet many don’t realise how lucky we are to have seals as part of our wildlife. With numbers of around 120,000, grey seals in Britain represent 40 percent of the world’s population, and globally there are fewer grey seals than African elephants. So, it is extremely special that we have so many living here.

Despite spending a large amount of time out at sea feeding, seals regularly come onto land to digest their food and rest. In fact, they spend at least eight to 10 hours out of the water every day. Unlike common seals which prefer estuarine habitats, grey seals like to spend their time on isolated, rocky shores. This, along with feeding in cold open waters, is why they love what the North East coast has to offer. Basically, they’re after places where they can just be left in peace, which is something we can all relate to.

Spending their time within a range of around 100 kilometres, seals are solitary animals, coming onto land individually wherever and whenever they choose. A seals’ haul-out site is a land base where you regularly find a large congregation of seals. The dynamics of these haul-outs are very specific, and careful consideration is given before a site is selected. A few seals will scout the island out initially to see if it’s suitable and then, once it’s got the ‘seal of approval’, gradually more will join.

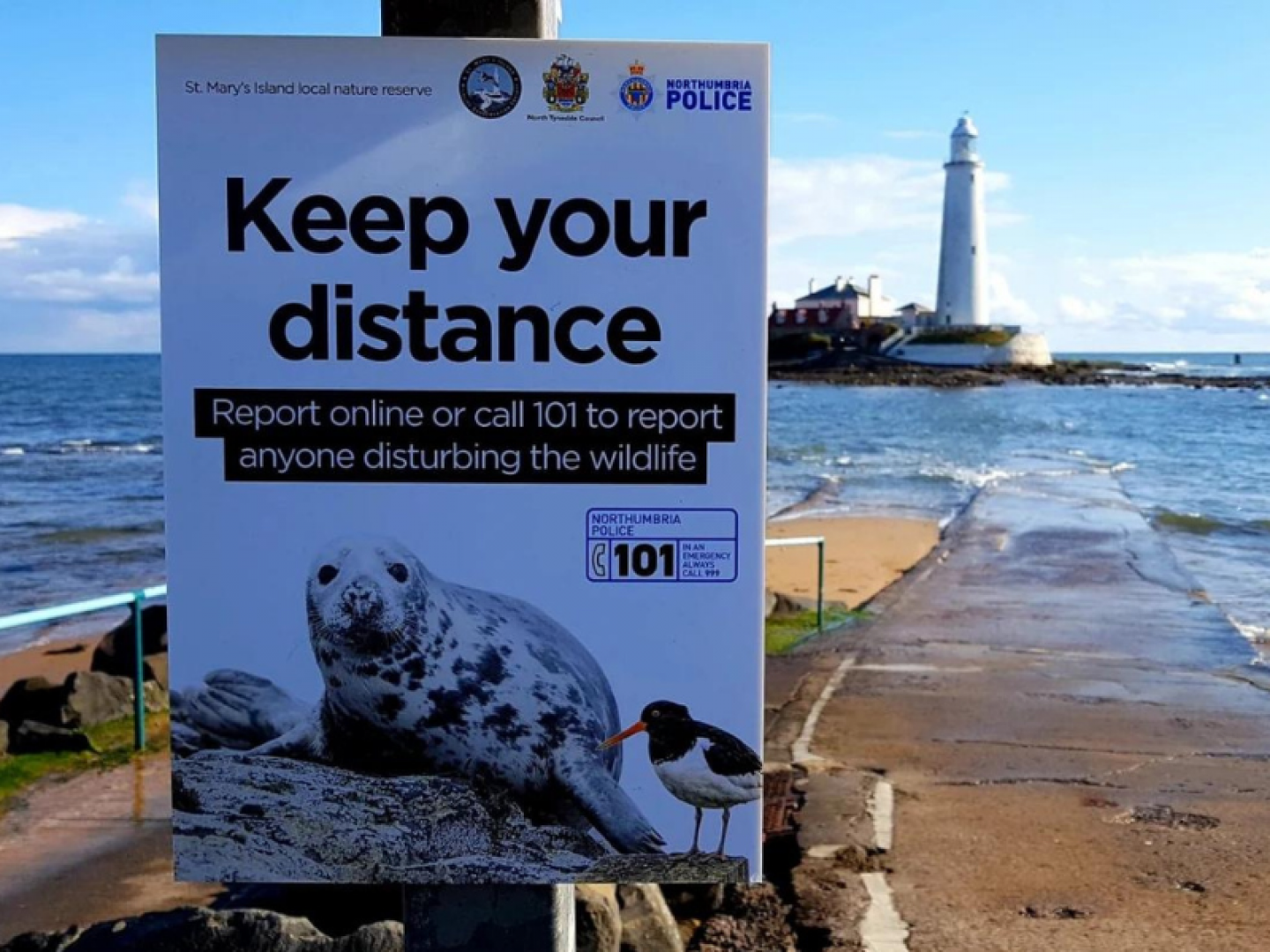

These sites are often isolated and uninhabited islands, with well-known examples including the Farne Islands, Coquet Island, and St. Mary’s Island at Whitley Bay – an easily-accessible island which has been chosen by our grey seals as one of their go-tos.

With a Grade II-listed lighthouse in the centre of the island, and a tidal causeway joining it to the shore, the island gets many human visitors each year. Classified as a nature reserve, North Tyneside Council have set out a wildlife managed zone on St Mary’s, which is an area set aside for the wildlife, with visitors asked to avoid entering. Luckily, the raised platform of St. Mary’s lighthouse creates a great viewing area, with fantastic views across the surrounding rocks so we can see the seals from a safe distance without having to encroach on their space.

Because so many of us stayed away from our beaches during lockdown, seals became even more commonplace. With many places quiet due to Covid restrictions, herds of seals (sometimes called bobs) were being spotted in larger numbers all along the coast, as well as on the island. These ‘growing’ colonies were not a result of increased breeding but because, with less human presence on the beaches, the soulful-eyed seals were becoming braver and venturing increasingly nearer to the shoreline.

Chair and co-ordinator of St. Mary’s Island Wildlife Conservation Society (SMIWCS) Sal Bennett, explains that the lower footfall allowed the seals space to roam closer to the shore. ‘I can only describe it as a sigh of relief on the part of wildlife,’ she says. ‘During the first lockdown, the seals had so much more space and had the confidence to explore new places without being scared off.’

Seals feeling more comfortable in our waters was one of the many positive environmental impacts of the pandemic. However, it, unfortunately, didn’t last and with the easing of the lockdown, human disturbance is once again one of the biggest threats to seals. With restrictions on international travel making staycationing increasingly popular, people are exploring their local environment more, and there has been an unprecedented rise in visitors to the coast. In response to this, the number of seals being seen on St. Mary’s Island has worryingly plummeted once again. This is partly due to seals moving back to quieter places where they won’t be disturbed. Sadly, in other cases, seals are being spooked, and injuring themselves as they rush into the water.

‘There are more and more visitors seeking wilder places for the solace that we’ve all longed for during these very difficult times,’ Sal continues. ‘But if we don’t use these spaces carefully, there is a real risk that people will be responsible for damaging and disturbing those very places.’

Sal goes on to say that ‘connecting with nature is a phrase that is used a lot now, but if that isn’t done carefully then the benefit is only one-sided. It becomes less of a connection and more just imposing.’

There are certain times in an animal’s biological process when they’re most at risk. For grey seals, one of these times is a pupping season, from October through to January. Despite having an average lifespan of 30 or 40 years, many grey seal pups don’t even make it to their first birthday, with sadly only 25 percent likely to survive to the age of 18 months in a bad year. Unlike dolphins, where the calf stays in the pod for years, seal pups are only with their mum for around three weeks before they are left to fend for themselves. This means pups on the shore are really vulnerable, and as they’re so susceptible to being abandoned, need even more of a wide berth.

Another particularly sensitive time for seals is when they’re moulting. The moulting process only happens on land, so every time they’re flushed back into the water it has a detrimental impact on the already exhausted seal. ‘The thing about disturbance is not only are you preventing the animal from conserving energy, they’re actually having to use more as a result,’ Sal explains. ‘So it really can be the difference between life or death for these animals.’

People may try and get a close-up picture of a seal looking wide-eyed, and they may think it will only take them one minute then they’ll leave straight after. But that wide-eyed look at the camera is actually the result of disturbing the seal; the animal is watching you while it should be resting. And although that picture may only take one minute, so will the next person, and the person after that. It is therefore important for people to be educated, to understand the behaviour of these marine mammals, and be more aware of their welfare.

The natural behaviour of seals on the land should be scratching, yawning and sleeping. The seals we can see on land are there to rest, and (just as if we were to be woken up every five minutes during the night) if they don’t get those forty winks they become fatigued, and this exhaustion results in deteriorating condition and loss of body weight.

In April 2021, the Seal Alliance launched a campaign, backed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), aimed at educating the public about the devastating impact human interactions can have on seals. Boards and signs for the campaign have been put up at areas seals frequent on the North East coast. At St. Mary’s, in collaboration with Northumbria Police Marine Unit, they have their own signage with do’s and don’ts, as well as SMIWCS volunteers available on the island to ask for advice.

‘Feel free to find our volunteers and ask them anything. That’s what we’re there for and we’re happy to help! It’s fantastic that we have this wildlife; a nature reserve is a place for seals to make their home. However for that to occur we have to be willing to adapt our behaviour and give them not only the space they need to survive but also to thrive,’ adds Sal.

Promoting responsible wildlife watching is not telling people to leave seals alone completely, but instead just following some common sense advice in order to live alongside these unique mammals. For example, look out for and follow signs, avoid wandering into wildlife zone areas, look at them through optics using binoculars or a scope, keep quiet, remain downwind where possible so they can’t smell you, always keep dogs on a lead on beaches where seals might be, and if you’re carrying out watersports make sure you give haul-out sites a wide berth. These small things will have a huge impact on the welfare of our seal populations.

‘If you are visiting a place that is important to nature, be mindful of the fact that we’re the visitors and we’re going into their home,’ says Sal. ‘Human disturbance is a preventable threat, and we all just need to do our bit to protect our wildlife. We are so lucky to have these seals, so we really cannot take it for granted them being here.’

If you see an injured seal on St. Mary’s Island get in touch with one of the SMIWCS volunteers, and they will help you to do what is best for the animal. Or if you find a seal you’re worried about in a different area, call the British Divers Marine Life Rescue (BDLMR) on their 24-hour hotline. They will dispatch the nearest medic to assess the seal and see if they need rehabilitation, intervention or treatment, or whether it’s just a resting seal.

To find out more information, visit bdmlr.org.uk or stmaryssealwatch.com. The BDLMR 24-hour hotline number is 01825 765546.