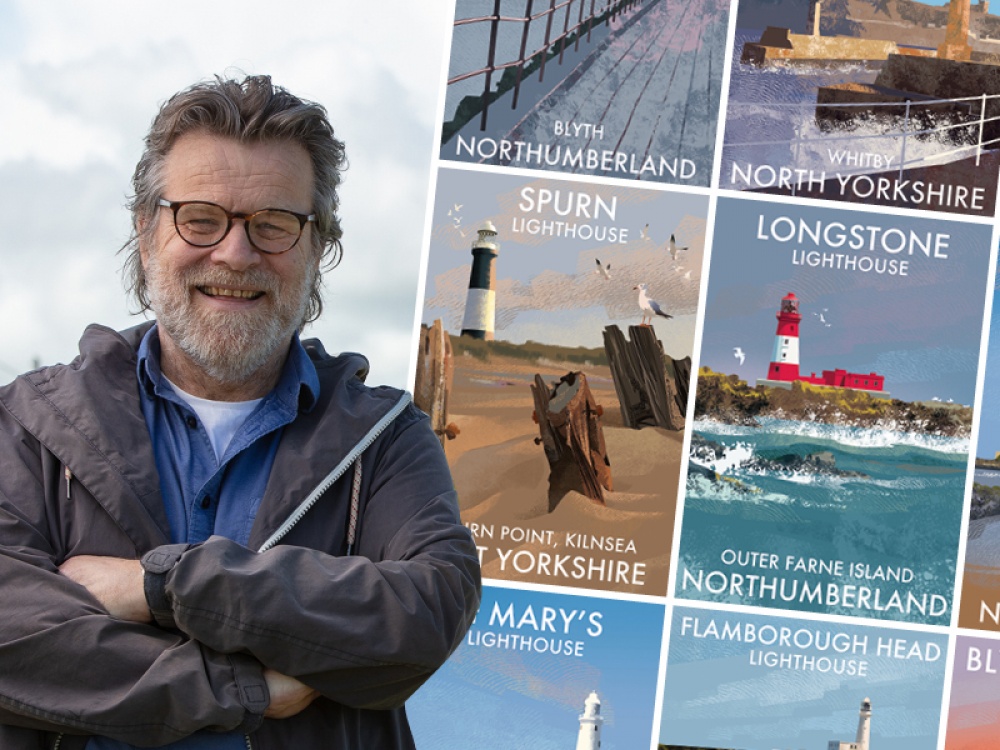

Meet Award-Winning Artist Roger O'Reilly who Illustrates Britain's Lighthouses

Inspired by the now iconic travel posters of the '30s and '40s, Roger has spent the last five years illustrating Britain's lighthouses

Roger’s career as a storyboard artist has seen him work in advertising and illustrate for movies and TV shows including the Vikings. In 2017 he began illustrating posters of lighthouses around Ireland’s south coast for friends and family as gifts which were really well received. ‘Before I knew it I had 20 done and just thought, why not keep going?’ he says.

Gathering his illustrations together and researching the fascinating history of Irish lighthouses led Roger to creating his award-winning book, Lighthouses of Ireland. ‘The book became very successful and it won Irish Book of the Year in 2018. Shortly after that I was on holiday in Cornwall and during some sketching around the coastline, I thought why not sketch a couple of lighthouses around Cornwall? Somerset looked good too, and before I knew it I had a map spread out and I was planning where I was going to go next,’ he explains.

Having spent five years illustrating more than 350 lighthouses, Roger has created a new collection of artwork based on his own drawings and sketches. His latest book, Legendary Lighthouses of Britain (which publishes early next year), includes some of these new illustrations, many of which feature locations which are right on our doorstep.

‘In a lot of cases, lighthouses are still in operation so they don’t allow visitors in, but they have one or two days a year where they do let people inside, certainly the onshore lighthouses. I’ve been lucky enough to get inside some of them and get up the top to see the lantern rooms in various lighthouses,’ Roger says. ‘From when I was a kid, I found lighthouses incredibly reassuring and on foggy nights I remember you would hear the ships with their fog horns attempting to come into port. You knew the ships were being looked after. The lighthouses themselves are a symbol, like a spot on a map where you recognise you’re home – even for us land-lovers, there’s a romantic notion about lighthouses which appeals to people.’

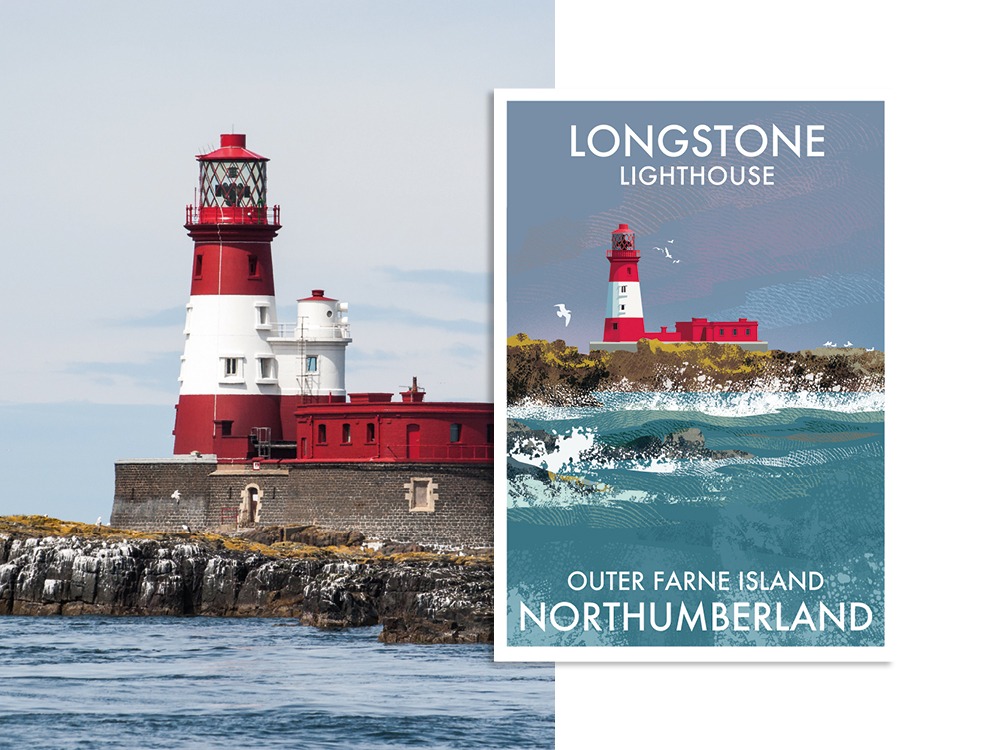

Read More: The Heroic Life of the Farne Island's Grace Darling

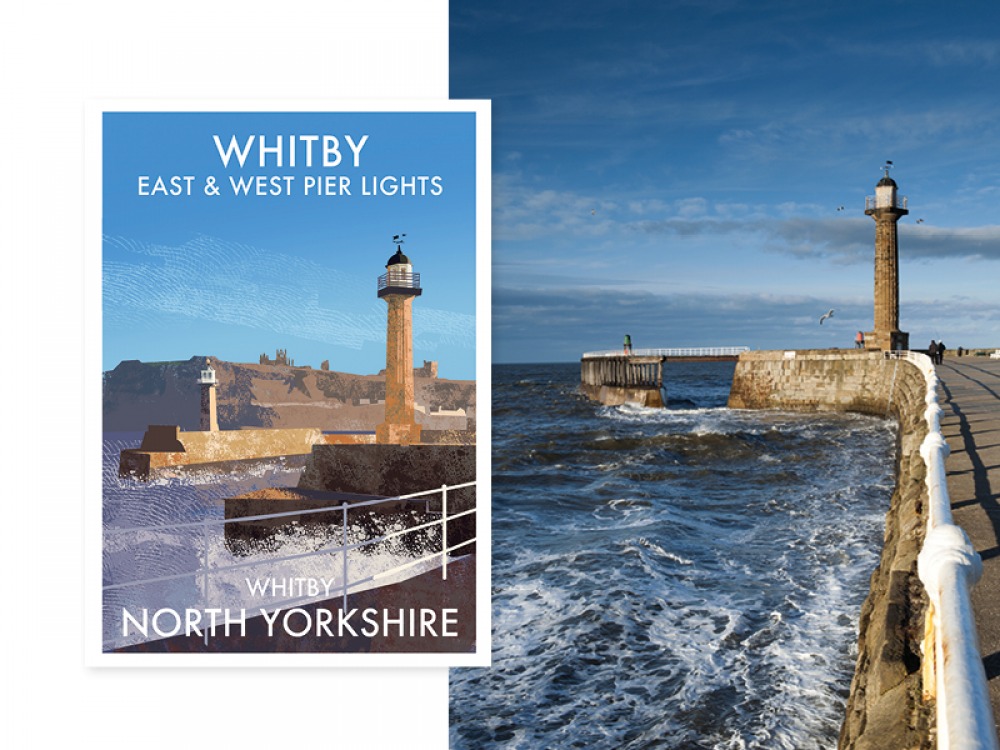

Deciding which structures to include in his latest book depended heavily on their build and their fascinating history. ‘Lighthouses come in all shapes and sizes. In Whitby there are two lovely lighthouses which almost look like pillars and they have great stories attached to them too. Lighthouses all vary so much and have been built over a period of around 250 years, so it’s hardly surprising that they have changed from one century to the next,’ Roger explains. ‘They speak of the sea and they are part of our built heritage, and it’s one of the things which makes the book important, it’s a reminder of just how important they are and asks the question: how are we going to look after them in the future?

‘The history is of enormous ingenuity and, I suppose, courage to build the lighthouses in the first place, and of course the people who manned them would have been incredibly resilient people. Not just the men but the families themselves – to grow up as a child of a lighthouse keeper must have been incredibly difficult,’ he adds.

For sailors, a lighthouse would be a welcome first sight of safe harbour, while during daylight they act as markers, beacons, and even destinations in themselves.

'A lot of the lighthouses are going to be retired in the next 20 years and we need to work out how we are going to preserve them'

This is part of what he hopes to achieve with his book. As well as his artwork, Roger has researched the history of each lighthouse and shares tales of their iconic maritime history. Posters of the lighthouses are also available to buy. ‘I think people are incredibly proud of the lighthouses in their locality. Often when I sell the prints, part of the reason people buy them is because they want to say “this is where I come from”. I think it’s fantastic to have so much pride in your area,’ he adds.

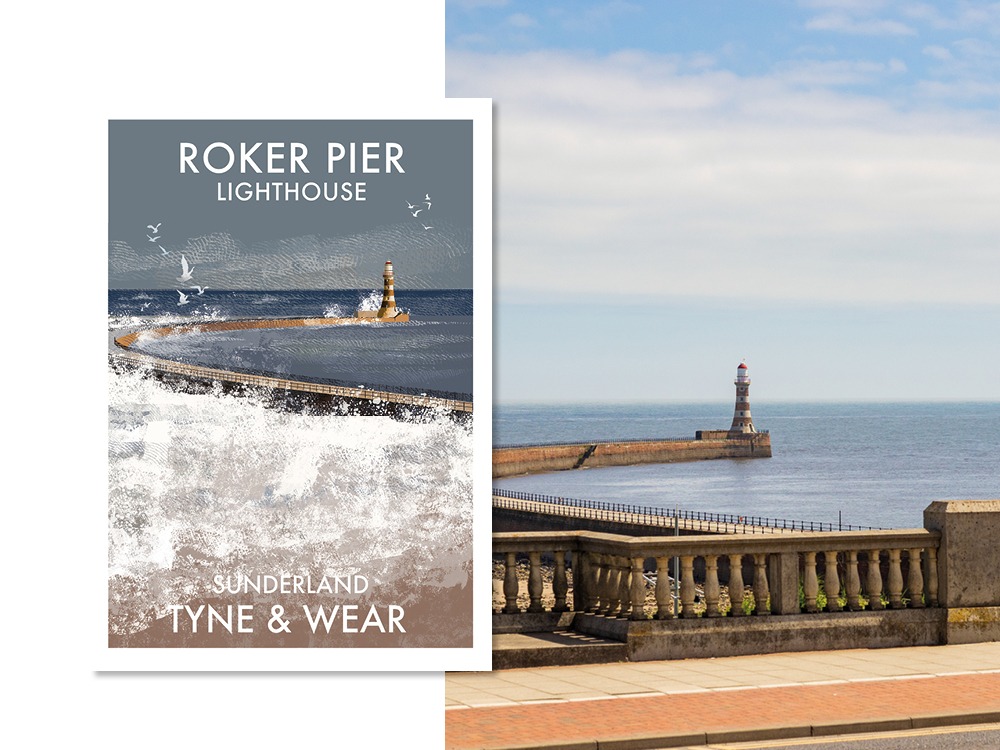

Here Roger shares extracts of five iconic lighthouses from Yorkshire and the North East with us. ‘I think Whitby is fantastic, Flamborough would be another favourite too, but I love Spurn because of the estuary. I grew up near an estuary and I love the feel there. The fact that the whole barge is shifting and changing I find fascinating. In a couple of years time that will probably be an island, but I think the places which these structures are in are so interesting. In the North East, I think Souter stands out because you can get to it and see it, of course, Roker is incredibly impressive, especially during a storm, but it's hard to pick a favourite.'

The illustrations are now available to buy from lighthouseeditions.com, and the book Legendary Lighthouses of Britain, including prints and stories, will go on sale in 2024.

During the 18th and 19th centuries Whitby was one of the main trading ports on the east coast. The West Pier, constructed in 1632, replaced a previous wooden pier and was followed in 1702 by the East Pier. The handsome Doric column we see today on the West Pier was built in 1831, but despite its attractive appearance, the light has an eerie history.

Lore has it that one stormy night the keeper noticed that the light had gone out – why he was somewhere else that he would notice it from afar is never explained! In any case, he hurried towards the tower and, soaked to the skin, sped up the steps to re-ignite the lantern. Having rekindled the light he sped back down the stairs (perhaps to resume a game of knurr and spell), but slipped on the now-greasy stone stairs and fell headlong into the void and departed this mortal coil. Some folk say that on a black blustery night, a lonesome figure can be seen making his way with a covered lantern towards the lighthouse before he disappears through the locked and bolted door.

Spurn Point is a low sandy spit of dunes and marram grass that extends about four kilometres into the mouth of the river Humber. Like all sandbars along this coast, it is at the mercy of the tide and storms, and over the last 300 years has moved westward and increased in length.

The first light on the point is reputed to have been erected by a hermit called William Reedbarrow in the mid-13th century, but no remains of his structure survive.

Centuries later in 1674 a London merchant, Justinian Angnell, gained permission to build a pair of coal-burning lights on the point. These were regularly washed away by the tides and had to be re-built. By the mid 18th century the bar had grown almost two kilometres to the south and the lights were now regarded as dangerously misleading so John Smeaton was commissioned to build a new pair of towers. These were a pair of swape towers, where the coal fire was lit in a metal basket or brazier and swung out over the edge of the tower on a wooden swape or wooden swivelled lever. Eventually the brickwork on the upper tower started to crack and in 1892 it was replaced by the present 39-metre lighthouse. Due to improvements in navigation, this light was discontinued in 1985.

Withernsea Lighthouse, built between 1892 and 1824, soars to an impressive 127 feet tall and it is one of only a handful of lighthouses built inland. The climb to the top entails a challenging 144 steps but you are rewarded with spectacular views over Withernsea and East Yorkshire.

The lighthouse is located nearly a quarter of a mile from the shoreline. At the time it was built, there was nothing between it and the sea but sand dunes, and the fear of coastal erosion led to it being positioned well back. The houses that surround it didn’t exist at the time and were all built when the promenade was later extended along the sea front.

Formerly owned and run by Trinity House, after 82 years’ service it ceased operation on 1st July 1976 and is now a museum and is open to visitors. The lighthouse keeper’s cottage at the base features RNLI and HM Coastguard exhibits, with models and old photographs. These record the history of ship-wrecks in the area and detail the Withernsea lifeboats and crews who saved 87 lives between 1862 and 1913. It also depicts the history of the nearby Spurn lifeboats.

By the late 19th century Sunderland was a thriving centre of shipbuilding and commerce and had outgrown its diminutive north and south piers. Plans were put in place to create a new enclosed outer harbour, protected by two elegant curved breakwaters projecting from the northern and southern shores.

Though both piers were begun at the same time, priority in construction and material was given to the New North or Roker pier and in the end, the First World War intervened and prevented the completion of the south pier. It had been intended that there would be two matching lighthouses each side of the harbour entrance, but the twin tower was never built.

The lighthouse at the end of the New North pier was completed in 1903. Known as the Roker Pier Lighthouse, the 75ft tower is composed of naturally coloured red and white Aberdeen granite, giving it its distinctive striped bands. The lighthouse is topped by a gallery and gleaming white lantern featuring a black domed roof. Completed in 1903, at the time it was estimated to be the most powerful port lighthouse in Britain.

In 2012, a programme of extensive refurbishment to the pier and lighthouse got underway and despite a storm in November 2016 seriously impacting the restoration process, work continued and a new entrance at the mouth of the Pier Tunnel now allows safe access into the underground passages that were used in the past by the keepers to get to the lighthouse in stormy weather.

Longstone is probably best known as the home of Grace Darling, the heroine who alongside her father braved a ferocious storm in a modest row boat to rescue survivors from the stricken ship SS Forfarshire in 1838. The ship was on its way from Hull to Dundee carrying about 60 passengers and crew when its boilers failed and the ship began to drift helplessly and struck Big Harcar Rock over a kilometre from Longstone. Within 15 minutes the creaking hull had split in two and the rear of the vessel was swept away into the roaring sea, while the front was wedged onto the rocks. The wreck was seen by Grace from her home at the Longstone, but it was early morning before there was enough light to see that there were still survivors clinging to the rock. Grace and her father William decided to row out in ferocious weather to bring in however many souls they could fit into their small rowing boat. Grace sculled the boat backwards and forward to avoid crashing on the rocks while her father checked the injured and by 9am nine survivors ware safely recovering at the lighthouse.

Grace was celebrated as a heroine and her story was printed far and wide. She and her father were awarded the Gold Medal for Bravery by the Royal Humane Society and a Silver Medal for Gallantry from the RNLI.

Tragically, just four years later Grace would be dead of tuberculosis, dying on 20th October 1842. Her funeral four days later was attended by people who travelled from all over the country to pay their respects.