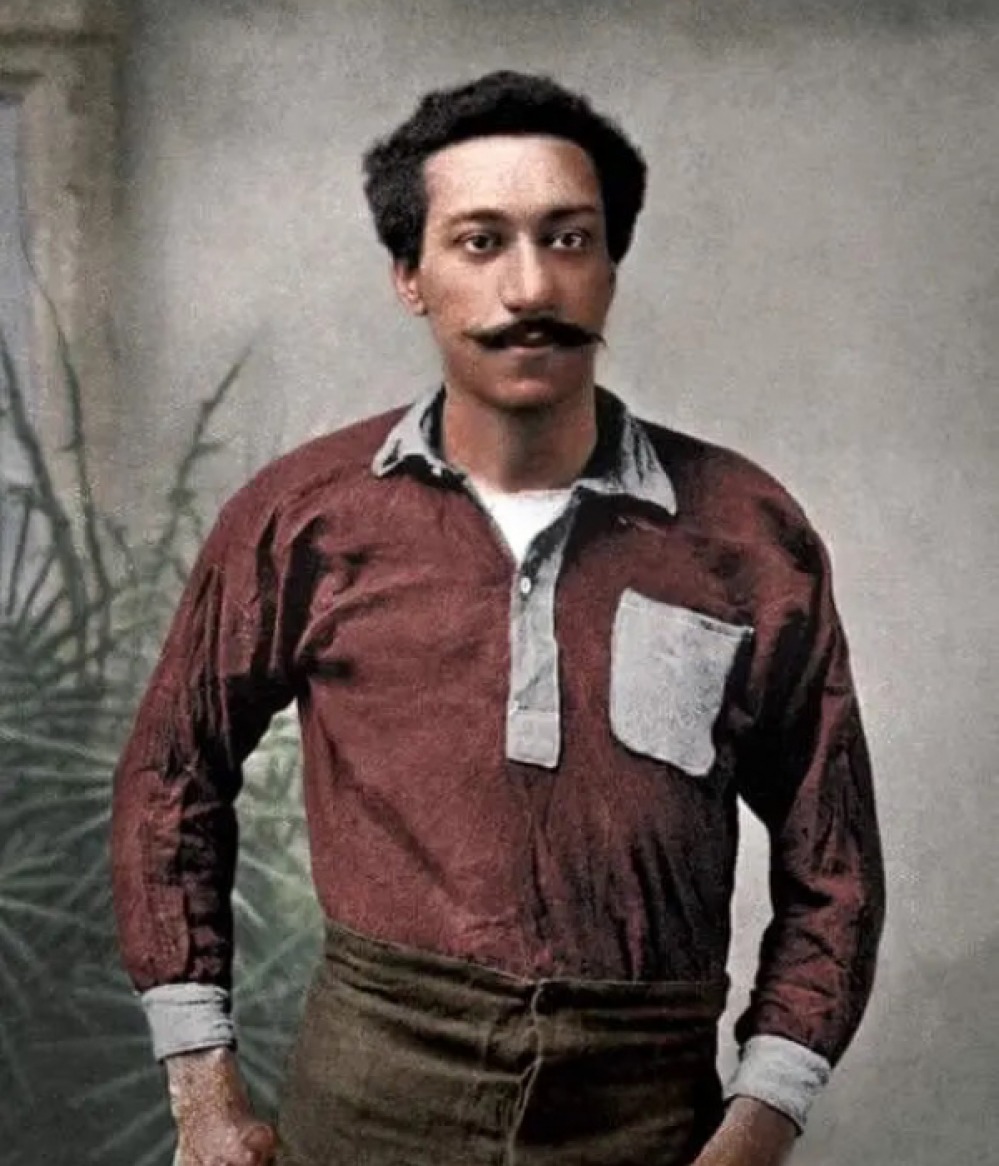

A New Film Celebrates the Life of the First Black Professional Footballer, Darlington's Arthur Wharton

Arthur Wharton was the first black professional footballer in the world, and he made his name playing for Darlington

Beloved stage and screen actor Derek Griffiths is set to play Wharton in the short film that local company Broken Scar Productions will begin shooting later this year. Supported through The National Lottery Heritage Fund, the project will enable people from the local area and across the UK to learn just who Arthur Wharton was, what he achieved, how his life ended tragically, and how his legacy is finally being recognised and appreciated.

Once released, the short film will be taken into schools, colleges and community hubs across the North East by the Arthur Wharton Foundation and used as a resource to educate about black heritage, equality and diversity.

The sad thing is, you’ve probably never heard of Arthur Wharton. Not many people have. For the final part of his life he was fairly unremarkable, grinding out a living working in coal pits, before dying of cancer and being buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave. Yet there was something very remarkable about his earlier career: in the 19th century he became the first black professional footballer in the world. It was only in 2014 that this accomplishment was acknowledged by the Football Association with the unveiling of a statue at the National Football Centre in Staffordshire. Among those who attended were Darlington-based artist Shaun Campbell, who campaigned for the statue and founded the Arthur Wharton Foundation, along with former players Les Ferdinand and Viv Anderson.

Read More: How Sheffield Charity is Using Sport to Keep Young People Away From Crime

Arthur was born in 1865 in Accra, the capital of the Gold Coast in West Africa, which has since become Ghana. His father was a Methodist Minister who had arrived from Grenada as a missionary, and Arthur’s mother was Ghanaian royalty – the family was far from poor and Arthur grew up among powerful and rich members of colonial society. These were turbulent times on the Gold Coast though, with several uprisings taking place against the country’s colonial intruders – the British. In 1875 Arthur escaped the violence when he was sent to a school in London (his brothers and sisters were also expensively educated). He returned to Ghana for a short while to attend a top local Wesleyan school, but in 1881 returned to England to study theology at a school in the Midlands.

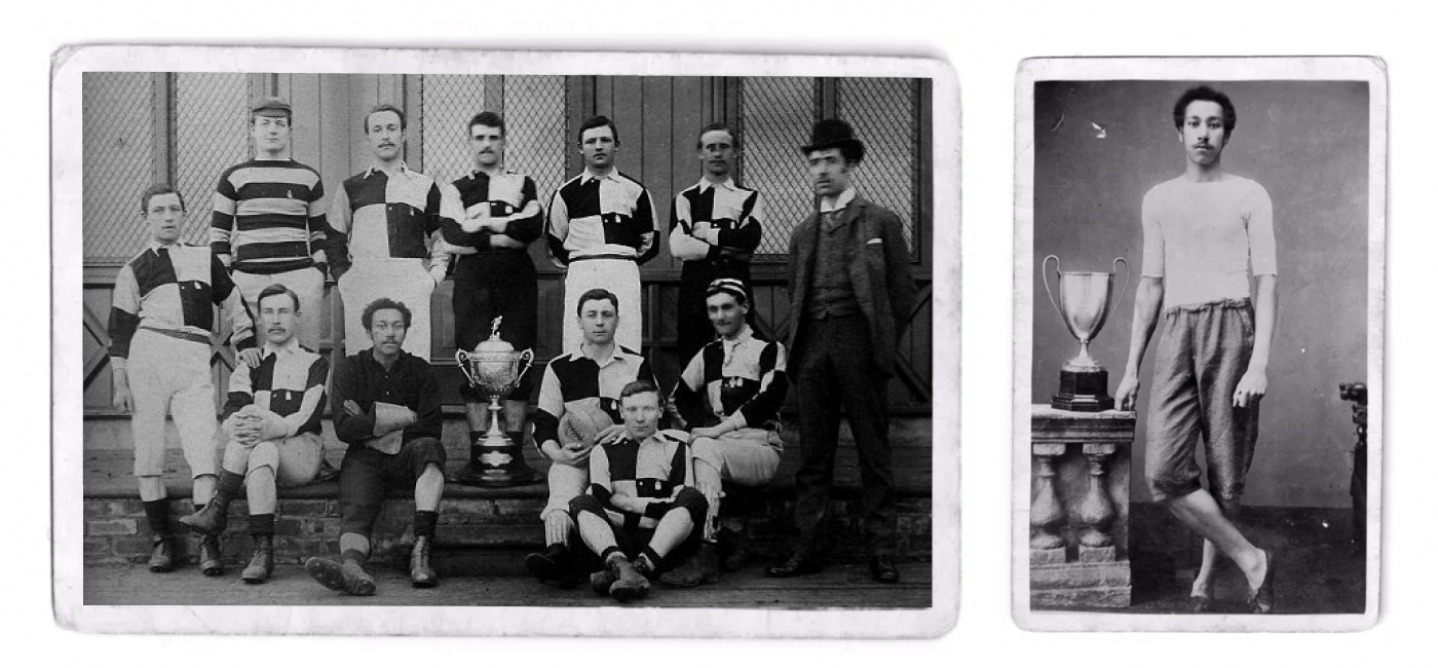

Arthur was expected to become a missionary, but it was sport that he loved. In 1884 he moved to Cleveland College in County Durham, aged 19, to train to become a Methodist preacher, but he was quickly distracted by football, cricket and rugby, and he ended up playing 32 matches in goal for Darlington, where he gained a glowing reputation, being described in the local press as ‘invincible’. He also excelled at running, and equalled the 100-yard dash world record in 1886 with a time of 10 seconds.

Read More: How a New Book is Celebrating Newcastle United Heroes

A commentator for the Darlington & Stockton Times wrote, ‘He has neither system nor style, but he runs like an express engine with full steam on from first to last with a result that makes both system and style unnecessary.’

His athleticism became legendary in the North and in 1887 he was poached to play in goal for Preston North End. It might seem odd that Arthur played in goal (he did actually play outfield sometimes), considering his pace, but at the time goalkeepers could handle the ball anywhere in their own half, which meant a fast keeper could rapidly move the ball safely to an attacking position. Arthur was very fast. He was also a bit naughty.

In a book called The First Black Footballer which was published in 1997, author Phil Vasili describes Arthur as having a ‘prodigious punch’ that he always connected with one of two targets: the ball or the opponent’s head. Some forwards didn’t like that. Almost everyone recognised Arthur’s goalkeeping talent though, and a journalist at the Northern Echo said he was ‘without doubt one of the most capable goal custodians in the country.’

In 1888 Arthur moved to Sheffield and became a professional runner – at the time Sheffield was a hub of athletics – and among his achievements was winning the Sheffield Handicap at the Queen’s Ground in Hillsborough in front of a crowd of thousands. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph described him as ‘travelling like a racehorse’. Despite never earning a huge amount through athletics, he was also a man of integrity.

‘I recollect a man once offering me £20 to lose a race,’ Arthur once told a newspaper reporter. ‘I asked him if he knew who he was speaking to, and he said, of course he did, but I told him I would run and if he ever made an offer like that again, I would report him to the Athletics Association.’

Throughout this time Arthur continued competing in cricket, rugby and cycling, but in 1889 he decided to concentrate on football. The Football League had been founded the year before and Rotherham Town had offered Arthur a professional contract. The crowds continued to love him. Many years later (in 1942) one fan belatedly wrote a small note to the Sheffield Telegraph & Independent, recalling, ‘In a match between Rotherham and Sheffield Wednesday at Olive Grove I saw Wharton jump, take hold of the cross bar, catch the ball between his legs, and cause three onrushing forwards – Billy Ingham, Clinks Mumford and Micky Bennett – to fall into the net. I have never seen a similar save since and I have been watching football for over 50 years.’

Some people didn’t appreciate his showboating and flair, and his skin colour would often be used as a way to undermine him, including racist comments in newspaper reports. He had great success at Rotherham though, helping them win the Midland League and promotion to the second division. In 1894 he signed for Sheffield United, tempted by the offer of also taking over the Sportsman Cottage pub – a typical sweetener job offered by football clubs at the time in lieu of a decent wage. Unfortunately for Arthur, Sheffield United had also signed a younger goalkeeper, William ‘Fatty’ Foulke, and for the first time in his career Arthur was second choice. He played just three games. In his last appearance for the club Sheffield lost 2–0. Arthur was blamed for one of the goals – he tried using his prodigious punch but missed the ball completely.

'Arthur may have died a forgotten man, but he’s remembered now'

Read More: We Meet Founding Member of Blaydon Racers Walking Touch Rugby Team

After playing for a string of other clubs, his last Football League appearance came in 1902. He ran a pub in Rotherham for a bit, before finding work in the coal of South Yorkshire. It’s believed that he worked at the seam for a few years, before ending up at Edlington near Doncaster, working at Yorkshire Main Colliery, where he worked as a haulage hand manhandling coal trucks – a dangerous and exhausting job. He spent the final 15 years of his life in that job, before he died at the age of 65 from cancer of the upper lip. He was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave, but the Doncaster Gazette reported ‘a fairly large attendance which was representative of all the sports and organisations he had been connected with.’

Arthur was largely forgotten by the nation, including a lot of us in Darlington, for a long while after that, until author Phil Vasili wrote his book about him in the 1990s. At the same time there was also a successful campaign to raise money for a gravestone for Arthur, which was led by Sheffied-based organisation ‘Football Unites, Racism Divides’. Six years later Arthur was inducted into the Football Hall of Fame in Manchester.

Arthur may have died a forgotten man, but he’s remembered now. Shaun Campbell, director of the Arthur Wharton Foundation says: ‘We are pleased to get this fantastic support from The National Lottery Heritage Fund and we are sure our project A Light that Never Fades will help people understand and appreciate the impact and legacy that Arthur Wharton left behind.’

To find out more visit arthurwhartonfoundation.org