Take a Peek at The Norman Cornish and L S Lowry Artwork on Display at The Bowes Museum

More than 50 paintings, drawings and sketches by artists Norman Cornish and L S Lowry are now on display at The Bowes Museum

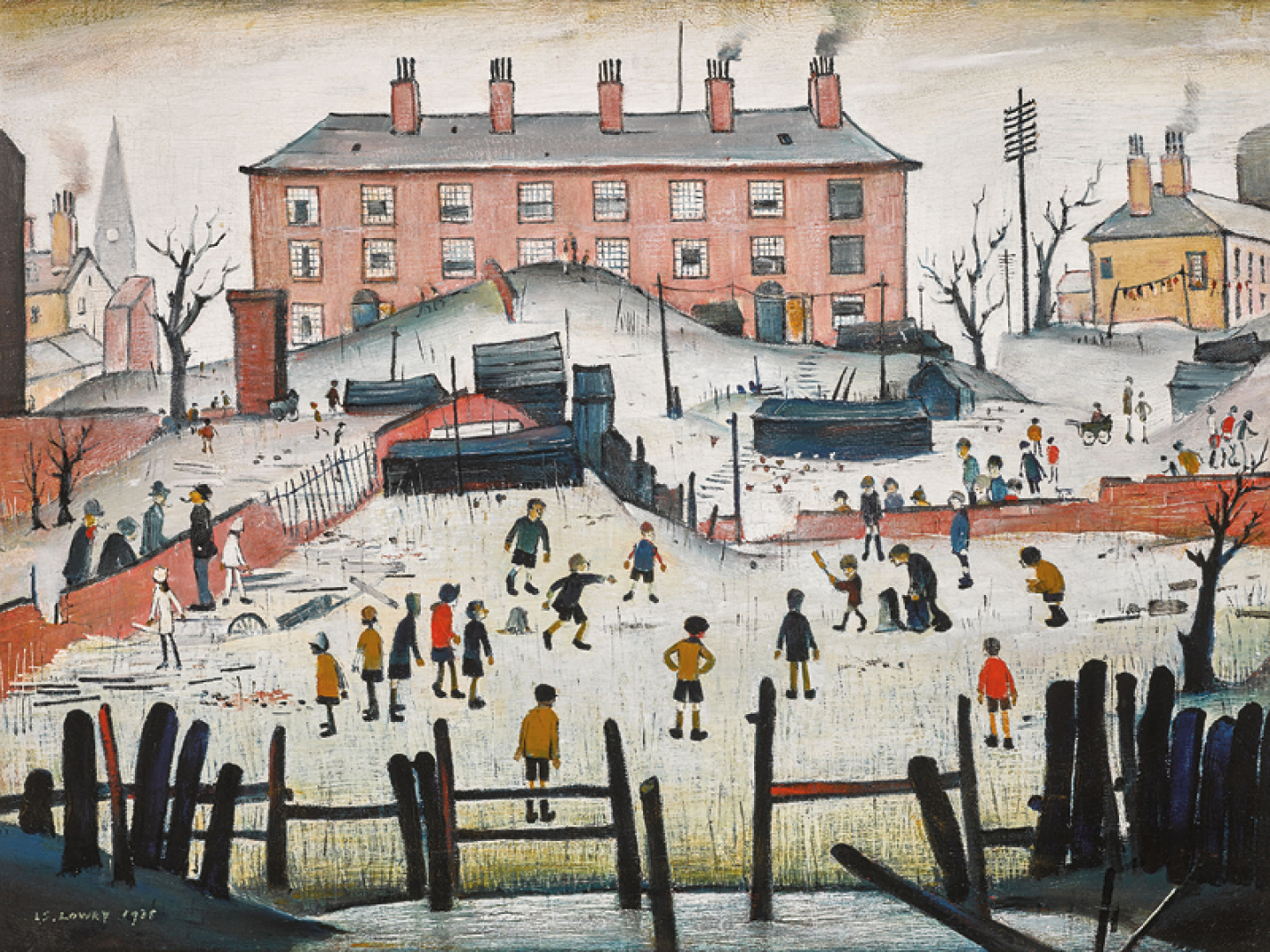

Two of the most famous artists of the 20th century, Cornish (a mining artist from Spennymoor) and Lowry (a Mancunian painter who frequently visited and depicted the region) were clever storytellers. In this new exhibition, featuring 35 rarely or previously unseen artworks, the artists’ love of the North is clear, and their takes on the region are clearly documented through their own unique and very different artistic lenses.

Hannah Fox, executive director of The Bowes Museum, describes Kith and Kinship as ‘a really wonderful celebration of the North’ stemming from a long-term relationship the museum has formed with Cornish’s family. The museum hosted a retrospective exhibition during the Norman Cornish centenary celebrations in 2019 which attracted more than 58,000 visitors.

‘That was an incredible moment for the family and for my father’s legacy,’ says Norman Cornish’s son, John, who describes Kith and Kinship as a continuation of that exhibition. ‘I think it’s great to see Lowry and Cornish together because you can compare and contrast their styles and how they felt about their communities. I think it’s a really big moment for my father and for his fans.’

The two artists were contemporaries and despite their 32-year age gap, John says they regularly met at the Stone Gallery in Newcastle where they exhibited together for more than 15 years. A pencil drawing of the gallery features in this new exhibition. ‘Lowry kept himself to himself,’ says John. ‘He was an outside character looking in. He was a quiet man who stood back and observed through his own perspective. My father was exactly the opposite. He was working in heavy industry from the age of 14 and as such he was part of the working community. He was very much inside looking from within. That’s why you get such different perspectives from these two different artists who were reflecting with their own eyes on the way they felt about the communities around them.’

Vicky Sturrs, director of programmes and collections at The Bowes Museum, has been exploring how the museum can showcase the North in different ways by displaying their works. ‘We’ve got lots of industrial and mining scenes which people will absolutely know Cornish and Lowry for, but we’ve also got some more tender and intimate pieces that you might not have seen from those artists, or that have been in private collections,’ she says. ‘We really wanted to show some fan favourites and hidden treats.’

Visitors to the museum will see the artists’ distinctive styles represented through paintings, drawings, sketches and film. ‘I think that’s going to show a much more intimate side to each of these artists,’ Hannah adds. ‘We’re presenting that alongside letters and quotes from both artists as well, and we do also have some interesting pieces, like some of Cornish’s sketchbooks, to show the process of making the work.’

Hannah and Vicky are also excited to be able to share a newly-discovered, never seen before self-portrait by Norman Cornish that was unearthed during conservation work. ‘That’s such an exciting moment,’ Hannah says. ‘Obviously, as an artist, there was a reason he turned it over and painted on the other side, but nevertheless it shows a moment in his progression as an artist and adds another portrait to a list of 28 known self-portraits.’

When we speak, John highlights a piece of his father’s work for sentimental reasons. ’It’s my mother telling me a bedtime story when I was about three or four years old,’ he says. ‘It’s a very small charcoal sketch. She’s telling me a story with her hand round my side facing the viewer, holding me close. It’s a beautiful composition, and it makes me feel very emotional. It’s a lovely, sentimental picture which I treasure and that’ll be there at the exhibition, alongside [other] powerful scenes.’

John believes it’s important to continue sharing both artists’ works. ‘For example, if someone of my generation goes to see the works they’re very nostalgic and they’re drawn into it like a window to the past and they stand, and reflect and talk and it’s quite an emotional experience,’ he says. ‘For them it’s important that they can show their children and their grandchildren what it used to be like for them. I think it’s important that we can reflect on our elders and their lives. When we’re gone, it’s important they continue to share the work because social historians will be able to look in a greater depth perhaps at the communities of the North.’

From August to November the museum will host a series of events running alongside the exhibition, encouraging visitors to explore its theme. ‘Talks will unpick the exhibition and the thematics from different angles,’ Vicky explains. ‘Members of the Cornish family are involved in that. We’ve also got some experts on Lowry and experts on the idea of industry and the environmental impact of that. We’ll look at mining community life and the legacy of that and what it looks like today. We’re also celebrating some of the drawing techniques throughout the summer in our learning programme. We have a brand new gallery space on our ground floor and visitors will be invited to test out lots of different materials throughout their visit as well.’

Vicky and the team hope to continue to attract visitors to The Bowes Museum by replicating and adapting what founders Joséphine and John Bowes started in their collecting practises. ‘There’s information in our archive that tells us Joséphine was collecting so many works by living artists and emerging artists as well,’ Vicky says. ‘She was going around fairs and salons, marking things in catalogues that she wanted to purchase for the museum to bring to the people of Teesdale. We’re really using that as a sort of north star. Joséphine gave us this remit to be relevant. She gave us that as an absolute gift. It’s about asking, what do the people sitting in our role and in our community’s shoes in 100 years need in a collection that we can represent for them and get for them now? That’s what’s so exciting.’

Hannah believes the collection Joséphine was creating had one of the greatest representations of contemporary art in the 19th century. ‘Joséphine died before the first impressionist exhibition and yet she was very clearly identifying impressionist artists as the next big thing,’ she adds. ‘She was a futurist and a trendsetter and she was also really interested in people. We’re looking at that in terms of how we represent contemporary artists of recent years and also thinking about that in how we look at exhibitions going forward – considering where we are supporting and uplifting the artists of the future, and also how we do that in dialogue with the artists of the North of England.’