Sheffield-Born Photographer Showcases Life Through the Lens of the Black British Experience in Exhibition

What is black Britain? Sheffield-born photographer and writer Johny Pitts has joined poet Roger Robinson to search for an answer

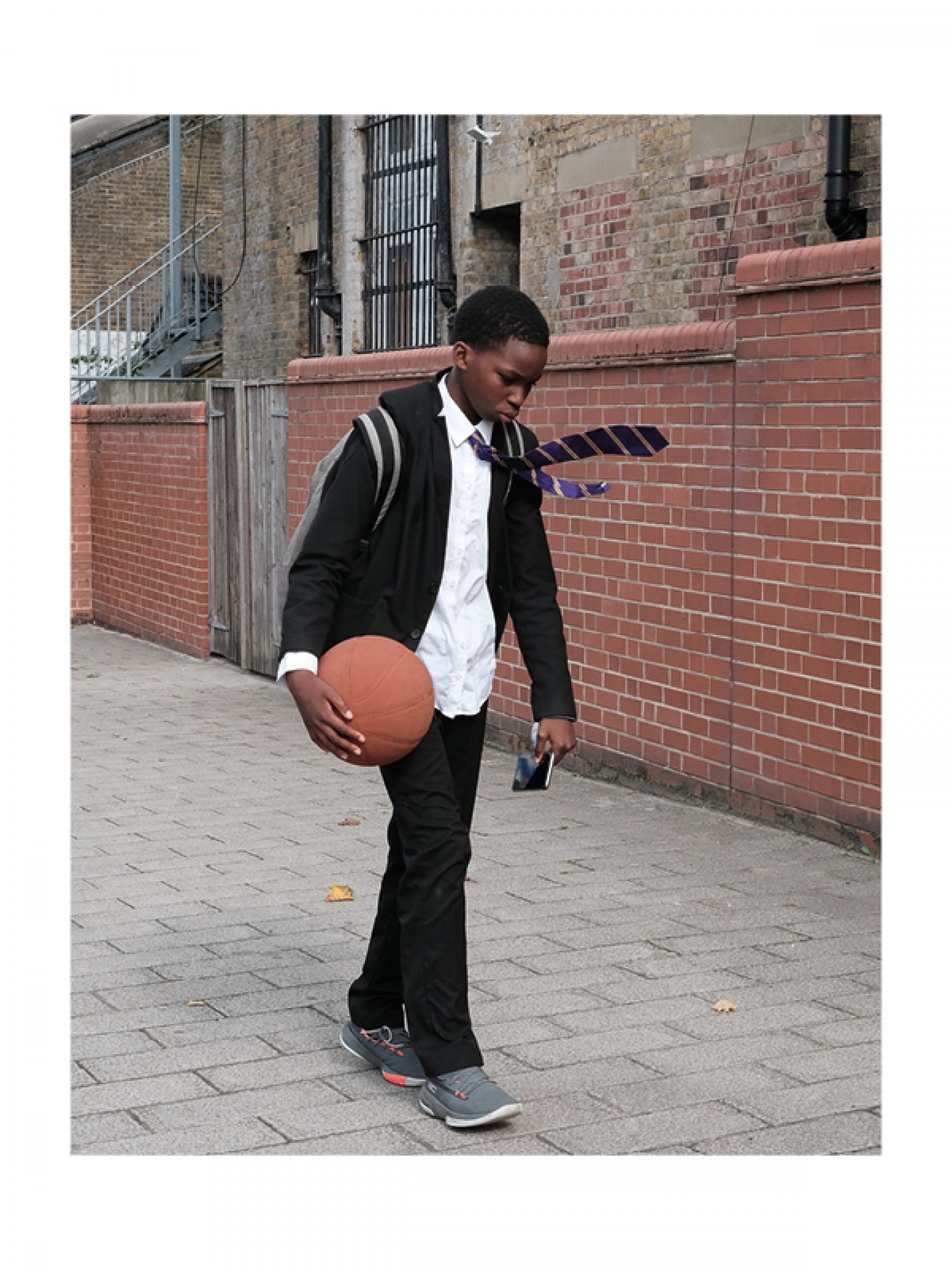

The works produced in response to this are on display alongside Johny’s images of Sheffield’s Firth Park, where he grew up. Side by side, they explore the idea of home through the lens of the black British experience.

A self-taught photographer, Johny describes himself as a ‘Northern Soul baby’. ‘My dad was an African-American musician who came over touring with his band and performed in many of the working men’s clubs, which is where he met my mum (who loved soul music),’ he explains. ‘I grew up in a very multicultural area and, up to a certain point, it was a really good place to grow up. Up until my teenage years, it felt like (all things considered) a multicultural success story. As we got older, some of my friends started getting into trouble and that’s when we started to hit some glass ceilings.

Read More: Sunderland-Born Inventor Brings Local Children's Inventions to Life

'A lot of my work as a photographer and writer has been about trying to piece things back together and trying to reconcile communities'

‘Even though I didn’t face much direct racism growing up, I did start to see racism embedded into institutions – systemic racism. A lot of the multiculturalism that existed started to disappear. After 9/11, a war on terror ended up becoming a war on Islam and I saw a lot of my Muslim friends really struggling with the prejudice they were facing. Then, in the global financial crisis of 2008, people were looking for scapegoats when it came to immigration. Instead of attacking companies who were looking for cheap labour and exploiting people, people who had a different accent or skin colour were being victimised. My great upbringing started to fall apart, and I think a lot of my work as a photographer and writer has been about trying to piece things back together and trying to reconcile communities.’

Read More: How Sheffield Charity is Using Sport to Keep Young People Away From Crime

Johny says his photography has the power to subvert expectations. ‘A lot of the time you might see photographs of mine that include things you would usually associate with right wing propaganda: a Union Jack or football paraphernalia, for example,’ he explains. 'But I’ll reinterpret it and try and put it in a different context. Photography is a great way to play around with ideas visually.’

Johny and Roger had been talking about potential collaborations for years, but now seemed like the right time to do it. ‘With all the things that have been going on in the UK (austerity, Grenfell Tower, the Windrush scandal and the Black Lives Matter protests), it seemed to be a really important time to think about black Britain – what it means to be black now, what it means to be British now and what it means to be black British now,’ Johny explains. ‘A lot of polemic books have been released with a lot of political analysis but we wanted to do something poetic. Sometimes the problem is that the work doesn’t always speak to everyone. Analysis hits people’s minds, but it doesn’t often hit their heart. We thought more of an exploration of these ideas might be a way in for more people –simply by looking at the images and reading the poems, they might get a sense of some of the issues facing us today.’

Creating an atmosphere with his work is also important to Johny. ‘Whether it’s the pen or the camera that I pick up, they both have the same energy that propels me. But, when writing, especially when working with an editor, you’ve got to get forward your argument in as clear a way as possible. What I like about photography is that you can be a little bit more ambivalent,’ he says. ‘I can take a photograph where there’s lots going on, but I can hint at certain things. Ultimately it’s up to the viewer to make sense of that.’

Johny’s work has been on display in the Graves Gallery since August, and he was able to create the atmosphere he had envisioned by using dim lighting and adding relics from his own home into the space. ‘That was the biggest thing for me,’ he adds. ‘You can take your photographs and spend a lot of time working out what should go where and you can talk a lot about how you’d like to frame them, but how do you create an atmosphere? I think that’s what both the book and the exhibition attempt to achieve – to create an atmosphere where people can come together and share ideas. I hope that, although people may not come away with clear conclusions (which we’re sometimes too quick to jump to), they come away with a feeling. That’s my argument: home is not a place, it’s a feeling.’

Having his work on display in his home town is something Johny is proud of. ‘Graves Gallery isn’t a place where a lot of my community would have thought about going to,’ he explains. ‘Growing up, it just wasn’t on our mental map of the city. My job is to put it on the map for my community; to say this place is for you, it belongs to you as much as everyone else. That was important with the curation of the space – to make it welcoming in a way that maybe galleries sometimes aren’t.’