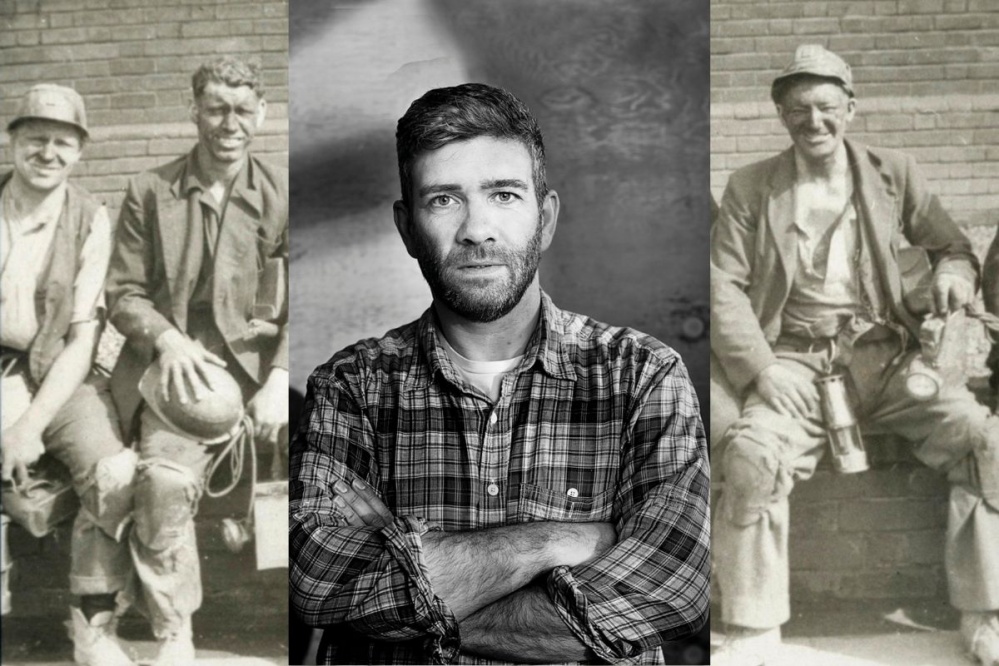

South Yorkshire-born Author Richard Benson Shares His New Novel The Valley

South Yorkshire-born author Richard Benson has written one of the must-read books of the year with The Valley. Roz Tuplin spoke to him about transforming his family history into a critical hit

So he moved to London, studied English and became a writer. Besides, he would have been, by his own admission, a rubbish farmer; 'I'm clumsy and mal-coordinated and not very cut out for it.'

In the late 1980s Richard became a freelance writer, and ended up working at The Face. For those who aren't old enough to remember, The Face was a zeitgeist-setting culture magazine with writers including Julie Burchill and the late Gavin Hills.

Richard made his mark during the publication's legal battle with Jason Donovan over an article that made claims about his sexuality. 'I got my break on the magazine during the case. They needed some junior people to get the magazine out while the staff were in court.'

Reflecting on that time, Richard says, 'I can actually see Donovan's point of view to be honest but people felt it was heavy-handed to force damages on an independent magazine that didn't make a lot of money.

'I think that induced a lot of people to support us and in the long run it benefited us.' Richard was Editor of The Face from 1995, overseeing its peak circulation and leaving in 2000 when it was bought by a multinational (four years later, it folded).

Read More: Northumberland Author LJ Ross Recommends This Book for Your Next Read

I wonder how a Northern farm lad coped with the big city. 'The funny thing is that in my village I was seen as not nerdy exactly but… a bit arty and not very practical. But if you move to London and you're from a farm and have a Northern accent people project onto you, they think you're earthy.'

Richard still lives in London but returns home regularly to see the family, enjoy the countryside and show his support for Leeds United.

Around the same time he left The Face, Richard's family sold the farm, so he went back to Yorkshire to help. 'A couple of years later I was talking to an agent and mentioned the sale and he said I should write about it. I thought he was kidding.'

That book, The Farm, became a number one bestseller, was Radio 4 Book of the Week, and was shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award. This year he published his second book, The Valley – a gargantuan, sweeping family history set over 100 years in the Dearne Valley that reads like fiction, but is in fact about Richard's own family.

He is influenced by writers such as American journalist Joan Didion, Victorian writers such as Elizabeth Gaskell and the Brontës, and Ronald Blythe, who wrote Akenfield, an account of life in a village in East Anglia.

Read More: Meet author Trevor Wood as he's shortlisted for the Theakston Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year

Richard was shortlisted for this year's Gordon Burn Prize, which is awarded to writers whose work is in the spirit of the great Northern literary journalist. For The Valley, he was particularly inspired by melodramatic family sagas, of the kind that his grandmother Winnie was an avid reader.

It took Richard six and a half years to finish the book, which describes in vivid detail the daily life of his family in the Dearne Valley mining community.

As well as dealing with the nature of working class life, the war, the changing role of women, the miners' strikes and pit closures, the book examines Richard's grandmother's spiritualism and his grandfather's amateur singing and drag act. It goes from the depths of the pits and the open countryside to betting shops, village hall dances and holidays by the sea.

Researching the book involved lengthy interviews with his family – a process that made him realise reality can be stranger than fiction. 'Some of the most interesting events would seem ridiculous in fiction. Early on, my great-grandfather Walter's life is saved in the war when a bullet hits a button on his jacket.

If you put that in a story it just seems ludicrous.' Later on, another scene sees his Auntie Lynda in hospital, told she will never walk again. With a lot of sheer mental will, and the love of her husband, she regains the use of her legs. 'A lady who through the power of love learns to walk again? It just doesn't work. But it's a really important part of the family story.'

Some of the stories are harrowing – domestic violence, fatal accidents in the pit, clashes with police and his baby brother's death as a result of a doctor's misjudgement must have been difficult to relive. 'It's funny, in a family you often have these stories that seem familiar but if you sit down and unpick them, lots of new detail emerges. I knew there was a vague story about a doctor being horrible and how my mum had gone to a séance afterwards with my grandma.

'But I didn't know the hospital had sent them all home when he was really sick, which I still find incredible. I felt I was uncovering things that had been left dormant, like the domestic abuse involving Roy and Margaret [his uncle and aunt]. I said to Margaret, "We can deal with this in a couple of lines," but she wanted to talk about it. She'd never really told anybody about it before.'

I wonder if he ever felt people were keeping things from him. 'People were very generous with their time, I was more struck by how open they were.' However, some stories got jumbled together, and people misremembered things. 'There's a story in the family that when my mum was born in May 1941, Sheffield was in flames.

'My grandma's in bed giving birth to my mum and she can look out of the window and see Sheffield burning on the horizon. I went and checked the dates in the newspapers. There were no bombs dropped on Sheffield for several months either side of my mum's birth. I had to say, "Mum, if Sheffield was burning then it was curiously absent from the newspapers the following morning."'

Read More: A Yorkshire Author and Adoptive Father on his Children’s Book

The book has been extremely well received, with some reviewers admitting to strong emotional reactions to the characters and their experiences. Often the strongest voices in the book are female. It's a novel which is unusually interested in what women are doing, or talking about, or feeling. When discussing his influences Richard cites several female writers, and the family saga is a genre traditionally consumed by women.

'I know it's fairly rare for men to like women writers. There's a different emotional dimension in a lot – not all – female writers that I respond to. Deeply unfashionable though it may be I like DH Lawrence for similar reasons. What I don't like is that macho very pared back writing you get, particularly with the cult of the male American writer. I find it so bloody boring! John Updike I can read about two paragraphs, I think it's absurd. Sorry,' he laughs.

But The Valley is also about 100 years of post-war masculinity – from touching descriptions of teenage male awkwardness to the rage of the striking miner. 'Men were having to decide how they might adapt to the world that was changing.

It's not like women are suddenly liberated and everything's fine, but overall there's a sense of an upward curve post war, whereas starting from the late 1960s you could posit there had been a downward curve for the men. I was interested in their ability to adapt – whether you could adapt or whether you got marooned.'

A good example of an adapter is his cousin Gary, who became a social worker after leaving mining, albeit with a shaky start. 'He got sucked into the pit, and when he finally got the professional desk job he'd always coveted, it absolutely did him in. He couldn't understand why they had meetings to decide everything.

In the pit they didn't have that luxury.' One passage of the book describes Gary entering the home of another ex-miner, a confrontation between the adapter and the marooned. 'On the face of it he isn't a pleasant guy, but he's trapped. It's sad to think of guys who get trapped and can't move forward.'

Read More: Whitley Bay-Based Stand-Up Poet and Author on her New Book and Representing Northern Women

The Valley is wonderfully evocative of rural and industrial Yorkshire. Is it a book that could have been written anywhere, or is it distinctly Yorkshire? And Northern? 'It does feel Northern to me,' says Richard. 'What's distinctive about its landscapes is the mixture of industrial and rural. In the South there's a strong sense of divide between urban and rural.'

For his next book, however, Yorkshire may no longer be Richard's muse. 'I wanted to do three family books and I have a great great uncle who emigrated to upstate New York and set up a farm in 1900.

His daughter is still around and she's a very interesting woman. Doing the family who went to America would close off that project for me.' He pauses, then adds. 'But shorter – I don't fancy another six and a half years!'