The Renaissance Man

This February a selection of Leonardo da Vinci’s original drawings will go on show at the Laing Art Gallery

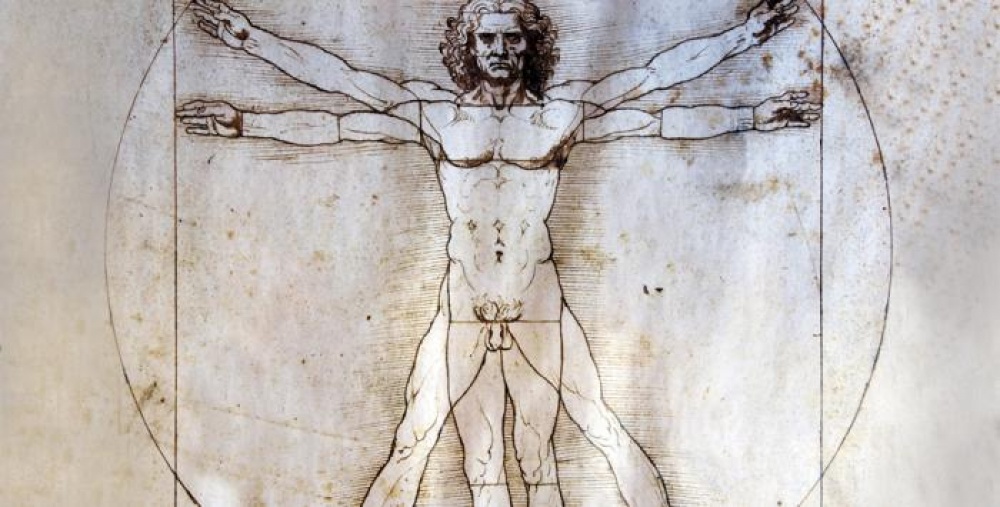

Uncontroversial statement: Leonardo da Vinci is one of the most important and influential artists ever. From the Mona Lisa to The Last Supper and the Vitruvian Man (the one with the man in a circle with his arms and legs splayed out), his artworks have become iconic. So much so that I once travelled all the way to Paris to see one in the flesh. But now, for two months only, 10 of his original (and rather revealing) drawings will go on display at the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle for all to see.

To say that I am excited is a bit of an understatement... In fact I was so excited that before 2015 was out I was banging on the door of the Laing Art Gallery demanding to know more. Step forward Julie Milne (the Chief Curator of Art Galleries at Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums) and Sarah Richardson (the curator of the upcoming exhibition), who are the Laing’s da Vinci experts.

‘They’re really special because there is so little left of what he did,’ Sarah says of the drawings. ‘A lot of his big, monumental projects were never realised. He didn’t publish books at the time, there’s only a handful of paintings left and even The Last Supper is disintegrating.’

These particular drawings were held as part of the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle (where Julie and Sarah first saw them), and they capture Leonardo’s work from 1490 to 1518, and as Sarah talked me through the context behind each drawing, I was led off on a fascinating journey of discovery about the great man.

Born in Florence in 1452, Leonardo was the illegitimate son of an Italian notary, which meant he wasn’t permitted to go to university. So, unlike his classically trained contemporaries who were influenced by great works of art, Leonardo turned to the world around him for inspiration.

‘He wasn’t basing his ideas about form on copying from other artists,’ Sarah explains. ‘He saw nature as the master. If they were going to paint nature, many artists would just copy leaves or flowers from another painting, but Leonardo wanted to make those studies for himself.’

This meant that before undertaking a grand work or commission, Leonardo would conduct ‘studies’ by sketching particular details repeatedly until they looked how he wanted them to. But don’t be fooled, this isn’t the kind of sketching that us mere mortals do. Despite the name, none of these drawings were done in pencil (‘There’s no rubbing out,’ Sarah laughs), instead he used ink, chalk, metalpoint and colour washes as he experimented with technique, style and construction all at once.

He used these studies to perfect various subjects, and 10 of them will be featured in the Laing’s exhibition. In one sketch you can see Leonardo practising blackberry stems and yellow rattle to be used in a painting of the myth of Leda and the Swan. In another he’s trying to capture ferocious horses for a mural of The Battle of Anghiari. Then there are playful cats for his own amusement.

But Leonardo was particularly interested in the human form: old, young, inside and out. We see him practising the crease of a baby’s knee for a portrait of the Madonna and Child. He created a wistful visage for St Anne (the mother of the Virgin Mary – who bares notable similarities to the Mona Lisa, which was created only two years later). And he tries to perfect the male form – the Laing’s exhibition includes A Male Nude, a sketch which seems to be a development of the famous Vitruvian Man. Though he had no formal training, it’s clear that Leonardo felt a need to measure himself against the classical artists of his day, and, interestingly, this piece was created in an attempt to rival Michelangelo.

‘It was part of a series of male nudes that he made,’ Sarah explains. ‘He was surveying all aspects of the figure as he’d just been commissioned to do a mural for the new Council Chamber of Florence, and Michelangelo, who was known for male nudes, would be painting a scene on an adjoining wall. He really wanted to get it right.’

Not satisfied with capturing human exteriors, he wanted to know about anatomy too. The exhibition features one of Leonardo’s most important studies, and perhaps one of the most important drawings produced in the 16th century – a pen and ink sketch of human organs.

‘Many artists observed dissections, but Leonardo actually did about 30,’ Sarah recounts. ‘This was an autopsy on a 100-year-old man who Leonardo had been talking to and died suddenly. Leonardo said he wanted to find out the cause of “so sweet a death”, and from his drawing it seems he probably had sclerosis. But this is a really important drawing because Leonardo, for the first time, is saying that the heart is the primary organ for the blood vessels, not the liver. Prior to that, many people thought that veins originated in the liver and took nourishment around the body, and while they didn’t understand oxygenation, they knew that arteries carried a vital spirit which was necessary for life. But here Leonardo was saying that both originate in the heart.’

It was this inquisitive mind that really fueled Leonardo. Other drawings in the exhibition show him conducting a study of the River Arno in Florence, trying to work out the mechanics of a monument he had been commissioned to produce for the Duke of Milan, and contemplating the apocalypse in the sketch of A Deluge (which was produced the year before he died).

Sadly many of the works for which these studies were conducted were never completed. ‘When he started a project, he went off in all directions,’ Sarah laments. ‘So although his projects are interconnected, he never got a lot finished. He says in his writings, you must forgive me for repeating myself but I can’t remember what I’ve said before. I think he was interested in developing his thoughts but not organising them and getting them properly set together.’

It’s a shame that there is no monument to Francesco Sforza with its gigantic horse or no mural of The Battle of Anghiari, which perhaps today would have drawn crowds in the same way as Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel. On the upside, you can at least head to your local gallery to get a glimpse into the work and life of one of the world’s most important artists, Leonardo da Vinci. I can’t wait.

See the Leonardo da Vinci drawings from the Royal Collection at the Laing Art Gallery

from 13 February to 24 April.

For more information visit www.laingartgallery.org.uk

Events Programme

EXHIBITION TOURS

Wednesday 9 March, Friday 18 March, Thursday 24 March, Thursday 7 April and Friday 22 April

Take a guided tour of the exhibition to find out more about Leonardo and his work.

ART CLASS: THE FIGURE

Saturday 12 March

A full day workshop led by professional artist Samantha Carey. All materials provided.

LEONARDO AND ANATOMICAL DRAWING

Thursday 17 March

Iain Keenan, Lecturer in Anatomy at Newcastle University, reveals the affinity between art and anatomy from Ancient Greek times to the Renaissance, culminating with modern medical education.

ART CLASS: LIFE DRAWING, A MALE NUDE

Saturday 26 March

Inspired by Leonardo’s ‘A Male Nude’, artist Tracey Tofield will demonstrate sketching techniques practised by Leonardo himself. Using mainly red pastel, sketch from a nude male model to develop observational skills.

LEONARDO: THINKING THROUGH DRAWING

Wednesday 30 March

Richard Talbot, Head of Fine Art at Newcastle University, celebrates the ingenious ways in which artists explore ideas, space and structure through drawing.

LEONARDO THROUGH HIS DRAWINGS

Thursday 14 April

Exhibition curator Martin Clayton (Head of Prints and Drawings at Royal Collection Trust) discusses the importance of drawing to Leonardo as artist and scientist throughout his career.

INK & DRINK

Thursday 14 April

Relax Renaissance style with music and craft. Design and build inky-drinky flying machines and enjoy curator-led tours of the exhibition.

ART CLASS: LIFE DRAWING, FEMALE STUDY WITH DRAPERY

Saturday 16 April

Leonardo spent countless hours as an apprentice drawing and painting drapery. Learn to sketch a draped model.

RENAISSANCE DRAWING MATERIALS AND TECHNIQUES

Wednesday 20 April

Jane Colbourne, Programme Leader, MA Conservation, Northumbria University, shows how Renaissance materials and methods shaped artists’ drawings.

ART CLASS: LIFE DRAWING, STILL AND MOVING DRAWING

Saturday 23 April

Leonardo drew directly from nature, capturing light, tone, depth and proportion. This class combines the skills of still life and life drawing to look deeper, using a variety of materials.

For more information and booking details for these events visit www.laingartgallery.org.uk