Travel Writer Who Seeks Out Sacred Places Visits Durham Cathedral

What happens when a stranger visits Durham Cathedral for the first time?

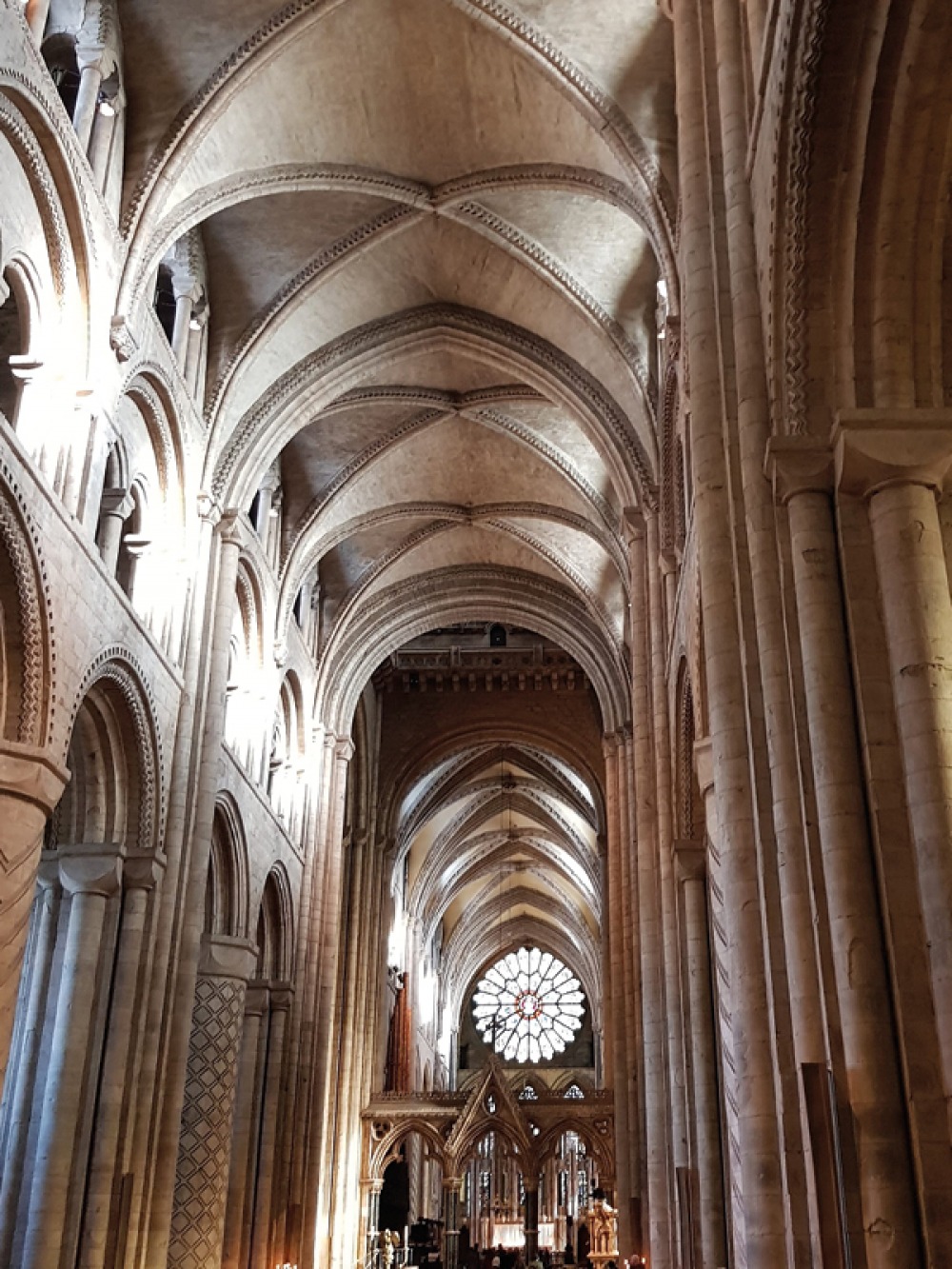

My first sight of the cathedral nave produced a powerful aesthetic jolt. It was not so much the sheer dimensions of the columns, piers and vaults as the shocking giant chevrons, lozenges and spirals carved deep into the stone, each one different. Nothing could be less traditional. In fact, I learnt that 11th- and 12th-century Norman architects had treated Durham as a sort of guinea pig for some of the outrageous creations which they could not have got away with back home across the Channel.

Bill Bryson claims to have barely heard of Durham when he caught sight of the vast, reddish-brown triplet towers while travelling on a train to Newcastle. ‘I unhesitatingly gave Durham Cathedral my vote for the best cathedral on planet Earth,’ he wrote in his 1995 Notes from a Small Island, explaining how he stopped off on a whim, walked down the hill from the station and unexpectedly fell in love with Durham. Requitedly so, apparently, since a decade later Durham University proposed to him in the form of an invitation to replace Sir Peter Ustinov as its Chancellor.

Read More: County Durham Gardener's Flower Gets Crowned Winner of the Threatened Plant of the Year Competition

Bryson was titillated by the cathedral’s stained-glass windows ‘spattering the floors with motes of colour’; enraptured by the ‘unutterable soaring majesty’ of the nave; and later allured by the ‘no less ancient and beguiling’ old quarter of Durham city. ‘It’s wonderful’, he concluded. Any visitor to Durham should be prepared to be similarly seduced.

Without a doubt, the cathedral and city are blessed with natural and artistic astonishments to set the heart aflutter. But would Durham have the same capacity to bewitch body and soul, were it not for centuries of sacredness? Bryson didn’t mention them, but were St Cuthbert and The Venerable Bede his secret matchmakers? Or, to put it another way, can a place attribute its special atmosphere to a saint lying entombed at a shrine? To the artists and architects who created that shrine to celebrate his sacredness? And to the millions who followed in faith and expectation?

These questions broke the stillness in my head, as I climbed the narrow stone staircase worn smooth by numberless pilgrim feet. I stopped before the plain marble slab where St Cuthbert lies. Alone and in virtual silence, I felt my boat well and truly rocked.

The story of Durham starts with St Cuthbert and remains intimately entwined with him. Cuthbert died and was buried at Lindisfarne in ad687 where his tomb attracted pilgrims from across Europe. In 875 the Lindisfarne monks fled from the marauding Danes, carrying with them Cuthbert’s body which they discovered to be miraculously uncorrupted. After seven years’ wandering, they arrived at Chester-le-Street, where Cuthbert remained till about 995 when another Viking invasion threatened and he was removed temporarily to Ripon.

Returning Cuthbert’s coffin to Chester-le-Street a few months later, the monks found that it suddenly became unaccountably and unmoveably heavy. Enter a forlorn milkmaid, plaintively pleading with them to help her find her mislaid cow, last seen on a nearby rocky outcrop almost entirely encircled by a meandering gorge of the River Wear. At which point the coffin’s weight relented, allowing them to follow the distressed damsel to the hill which forms the peninsula of ‘Dun Holm’. A sign! This is where Cuthbert intended to spend eternity.

‘Without a doubt, the cathedral and city are blessed with natural and artistic astonishments to set the heart aflutter’

Accordingly, they settled here and built first the White Church to house Cuthbert’s remains. This was soon superseded by one of the finest cathedrals in Christendom, with most of the present structure completed by the mid 12th century. Cuthbert lay in a glorious, gilded shrine behind the high altar, which became one of the most revered sites in England. Kings, queens, nobles and commoners in huge numbers from across Europe sought his intercession. His fabled sanctity grew exponentially as tales of miraculous healings mushroomed. The arrival (some say theft by Durham monks) in 1022 of The Venerable Bede’s remains from Jarrow further strengthened Durham’s power as a puller-in of pilgrims.

Durham’s geographic position also gave it strategic importance. After 1066 the Normans built a great castle next to the cathedral, from where they projected their power across northern England. The castle became a bastion in the wars against the Scots. Durham Castle became the seat of the ‘Prince Bishops’, who – such a long way from Westminster and Canterbury – enjoyed unfettered ecclesiastical, political and even military power over swathes of northeast England. Their reign survivedthe Reformation, when the Durham theocrats accepted the break with Rome and were incorporated into the Church of England. The monks either became lay workers in the new church order, or were sent packing.

Read More: See the Iconic Salvador Dali Painting on Display at Bishop Auckland's Spanish Gallery

The last Prince Bishop, William Van Mildert, was one of the great boat rockers. Affronted by the wealth and worldliness of the institution, he abolished the Prince Bishop title (becoming plain old Bishop of Durham) in 1836, and transferred his non-church powers to the Crown. He moved the Episcopal seat to nearby Bishop Auckland and used the castle to found Durham University – England’s third oldest, after Oxford and Cambridge.

Cuthbert, meanwhile, had had rather a rough ride. In 1540, during the Reformation, his shrine was vandalised by Henry’s henchmen and his remains buried under a great flagstone. In 1827 he was disturbed again; this time his skeleton was found wrapped in silk stoles and still wearing his pectoral cross. He was reburied in the tomb where he lies today, and the stoles and cross are on display in the cathedral’s Treasury Museum.

And what of Bede? For some three centuries his venerable bones lay next to Cuthbert’s. Then in 1370 he got his own magnificent shrine, in the Galilee Chapel at the western end of the cathedral. But this too was destroyed in the Reformation and, like Cuthbert’s, his remains were buried under a flagstone on the site of the shrine. His present simpler altar tomb, of polished black marble, stands on the same spot.

Read More: Luxury Jewellers, Berry's Celebrate Their 125th Anniversary With New Leeds Store

From whatever direction you approach the city, the cathedral is the dominant feature – vast in scale, beautiful in proportion, and awe-inspiring in sheer presence. Just imagine the effect it must have had on the local population when it rose above huddles of medieval hovels. The soaring walls, the high windows and the huge rise of the central tower must have been overwhelming.

Nowadays it is the university colleges along the Bailey that squat at the feet of this greatest of all Europe’s Romanesque architectural achievements. At the main entrance, on Palace Green, there is a sacred symbol to pause at before you even go in: the famous Sanctuary Knocker, a bronze lion’s head holding a huge ring in its jaws. In the Middle Ages any fugitives from the law who could reach the doors and grasp hold of the ring were guaranteed 37 days ‘sanctuary’ within the cathedral. Sanctuary meant entitlement to protection by the Church from any other authority and remained law until 1623.

Read More: Cramlington Photographer's Amazing Aerial Photos Capture The North East's Most Beautiful Locations

Once inside, it is probably best not to make a beeline for Cuthbert’s tomb. Rather, pause first in the nave. If the gigantic, 900-year-old pillars with their astonishing carvings knock the metaphorical (or even literal) stuffing out of you, try and picture the sheer energy they must have conveyed in the Middle Ages when they were painted black and scarlet. In those days there would have been no seating, just an expanse of stone beneath the rib vaulting.

Next, move to the far west end of the nave (the back), to visit Bede at his raised tomb in the Galilee Chapel. A modern wooden sculpture depicting Bede with a quill in his hand stands next to the shrine, looking on. His expression is benign and compassionate, tinged with wry amusement that he should be observing the slab inscribed with the words Hac sunt in fossa Baedae Venerabilis Ossa. In other words, the resting place of his own relics.

St Cuthbert’s shrine lies at the other end of the cathedral, beyond the high altar in the Chapel of the Nine Altars. The staircase leading up to the chapel, rising several feet above the Cathedral floor, is narrow and dark. However, at the top you spill into an area startlingly large, constructed so in the 13th century to accommodate the throngs of pilgrims who used to congregate here. Until the Reformation, of course, the shrine would have been a riot of gold and jewels, and heaped with bountiful offerings from royalty, nobles and wealthy pilgrims. Look around the chapel and you will still see treasures such as the stunning Rose Window, 30ft in diameter, depicting Christ surrounded by his apostles; and some beautiful black marble piers. There is also a rather striking white statue of Bishop William Van Mildert. But you might not notice any of these at first, because St Cuthbert’s powerful and magnetic presence washes over the senses of those receptive to his aura. However, his tombstone today is of simple grey stone, lying on the ground. Modern visitors can pay their respects, meditate in his sacred presence, pray or simply contemplate his life, legend and legacy, in whatever way works for them. Few will leave the chapel unmoved.

Huge wooden doors lead from the cathedral nave into the adjoining monastic cloisters, where rewinding through the centuries to pre-Reformation times feels effortless. Then, the covered, carved stone quadrangle around a small green was the habitat of cowled monks. Today, sightings of robed choristers – a similar species, in appearance at least – are common.

Among the surviving monastic buildings is the 14th-century oak beamed Monks Dormitory above the western walkway, which houses a collection of Anglo-Saxon stone crosses.

Finally, climb the 325 steep steps spiralling the top of the 217ft Central Tower for views over the winding River Wear and the expanses of County Durham, across which the monks carried Cuthbert and met a milkmaid.