We Take a Look Around the Newly Reopened Beningbrough Hall

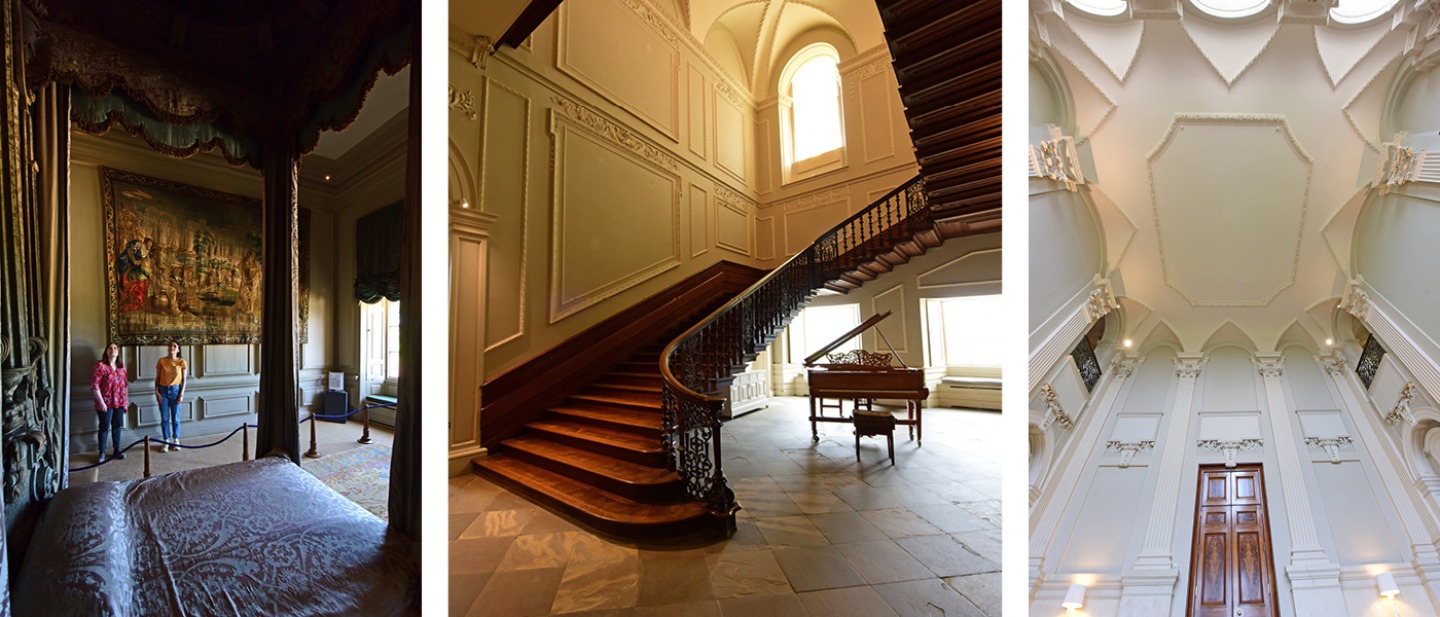

Following an almost two year hiatus Beningbrough Hall, one of the most remarkable baroque houses in England, has reopened with brighter interiors and even more fascinating stories to tell

Alexa Buffey is Beningbrough Hall’s collections and house manager, and she oversees the conservation of the Hall and the way it is presented and operates – caring for the house, its interiors and contents. ‘I’m relatively new to the property having started in October,’ she says. ‘It was interesting coming in at that stage because I’d never seen the house open before. When I started, the Hall was completely covered with scaffolding and protection and the floorboards were up. We’ve had the house completely rewired and had a new lighting system installed, which doesn’t sound like much but it’s one of the biggest lighting projects the National Trust has undertaken. There was barely any lighting in the Hall before so all of its amazing decorative features weren’t as visible as they should’ve been. All of these updates are helping to bring the Hall to life.’

With the new LED lighting, the quality craftmanship of the building is much easier to see (and therefore appreciate) and visitors are invited back to roam the Hall and imagine Beningbrough through the years. Through displays of key pieces of the collection, visitors can now better uncover the stories of those who shaped Beningbrough. ‘This Hall is an unusual one in that it doesn’t have one family story, there are quite a few people who have lived here and made Beningbrough their home for very different reasons,’ explains Alexa. ‘It’s meant lots of different things to different people.’ Since the current Hall was completed in 1716 it has been re-invented but it actually poses more questions than answers as, in comparison to other estates of this age, there are very few archives. What we do know is that Ralph Bourchier inherited the Beningbrough estate in 1556 and began building the first house – which remained a family home for around 150 years.

In 1700, John Bourchier inherited the estate, and in 1704 embarked on a grand tour of Europe. His time spent in Italy heavily influenced his plans for the current hall (which was completed in 1716) – the main cantilevered staircase and the fine woodcarving you can see today. Margaret Earle was the last of the Bourchier line and owned Beningbrough for more than 65 years, then left it to Rev. William Henry Dawnay, a distant relative and close friend of her eldest son. Lewis Dawnay inherited Beningbrough and added electricity to the Hall, but in 1916 it was sold by Guy Dawnay and bought by Lord and Lady Chesterfield. Lady Chesterfield remained there until her death in 1957. ‘It’s been a family home, a short-term home and a country residence for Lady Chesterfield,’ Alexa adds. ‘Lots of hunting will have taken place, and she bred racehorses; a quintessential country life. But crucially, during the Second World War it was where the RAF were billeted – a brief but very interesting time.’ The National Trust acquired Beningbrough in 1958.

‘Through displays of key pieces of the collection, visitors can now better uncover the stories of those who shaped Beningbrough’

Read More: Top Places to Visit Across the North East for a Cultural Day Out

Yorkshireman Ian Reddihough left a gift in his will to support the conservation and care of Beningbrough Hall, which has allowed them to undertake the recent works. Alongside the professionally designed lighting the Hall and a full re wire, other work includes addressing decayed timbers, repairs to ceiling and staircase plasterwork, chimneys and stonework and improvements to environmental controls and heating. Final repairs on the north front steps are expected to be finished by the end of July.

‘It’s much brighter,’ Alexa laughs. ‘When we reopened we had previously regular visitors who commented how much lighter the Hall is. We call it a refurbishment, but a lot of the essential work has been taking place behind the scenes. We’ve got written interpretations and pictures around the house that tell the stories of the families that lived here so visitors can find out more about what the house meant to them. It’s absolutely vital that the Hall is safe. We have to do everything we can to preserve it but also look at how we can tell its stories. It’s a beautiful building and it’s very visually impressive but what brings it to life is its human stories, and this project is offering us the chance to better tell those.

Read More: 10 of the Best TV and Film Locations to Visit in Yorkshire

‘On the ground floors visitors can expect to see furnished rooms and interesting objects including the seal that was on the death warrant of Charles I, and tells the story of how John Bourchier was one of those who signed the death warrant,’ Alexa says. Bourchier was too ill to be tried as a regicide and died just before the Restoration, escaping any punishment. His son rescued the property from the threat of confiscation by Charles II, keeping Beningbrough in the family. ‘That’s just one example of how Beningbrough’s small history connects to wider history.’

Another interesting story is that of WAAF Dorothy Preston (Gipsy) and Canadian airman Harry Olsen (Olie) who met in 1941 at the Alice Hawthorn pub in nearby Nun Monkton. The next year Olie was transferred to 405 squadron, based at RAF Pocklington, and the couple exchanged letters but never met again. Graffiti above the drawing room fireplace has their names and a (now faded) heart (which is being protected to prevent further fading). The story behind the graffiti was a mystery until a lady visited the hall in 1987 – that lady was Gipsy. Last year more graffiti was uncovered in the loft with Gipsy’s name and a heart.

‘The future for Beningbrough is to continue being ambitious with our programme of exhibitions to tell stories in new and exciting ways’

The Reddihough Galleries on the first floor of the Hall host changing exhibitions of contemporary and traditional artwork and visitors can look forward to a new exhibition in September titled Inspired by Italy, bringing together the work of Kate Somervell, a contemporary photographer based in Yorkshire, and Giovanni Battista Piranesi, an 18th-century Italian artist. ‘This exhibition ties in the Italian influences on the architecture of the house,’ Alexa adds. ‘Kate takes a lot of architectural photos of Venice at night time. We commissioned her to take some similar photos of Beningbrough to showcase those connections. We’re also focusing on Giovanni who’s an Italian printmaker and who made a print with a dedication to the Earls who were the last part of the Bourchier family that lived at Beningbrough. We haven’t got a copy at Beningbrough but we’ve been able to borrow one from Wimpole Estate.

‘The future for Beningbrough is to continue being ambitious with our programme of exhibitions to tell stories in new and exciting ways,’ adds Alexa. Meanwhile, the garden now has a pergola, ha-ha walk and (opening in 2024) a new Mediterranean garden (which will sit alongside the traditional herbaceous borders and the walled kitchen garden), and children are encouraged to let off steam in the wilderness play area.